Weekend Food For Thought WFFT

On Today's Menu: (1) US Inflation, Welcome to the AI Age, (2) Deep Dive into Robotics and Automation, (3) Geopolitical Realities for 2026, (4) Standard Bots, (5) What Comes After Mastery, and more!

Hello from Lisboa,

I hope you had an interesting and productive week.

Julian Simon stated that: “Discoveries may well be infinite: the more we discover, the more we are able to discover.”

Below flows some new ground for you to discover, may it lead you to new unmapped territories of insight…

1 Getting Visual

2 If You Read One Thing Today - Make Sure it is This

3 Consequential Thinking about Consequential Matters

4 Big Ideas

5 Big thinking

6 Choice Management

1 Getting Visual

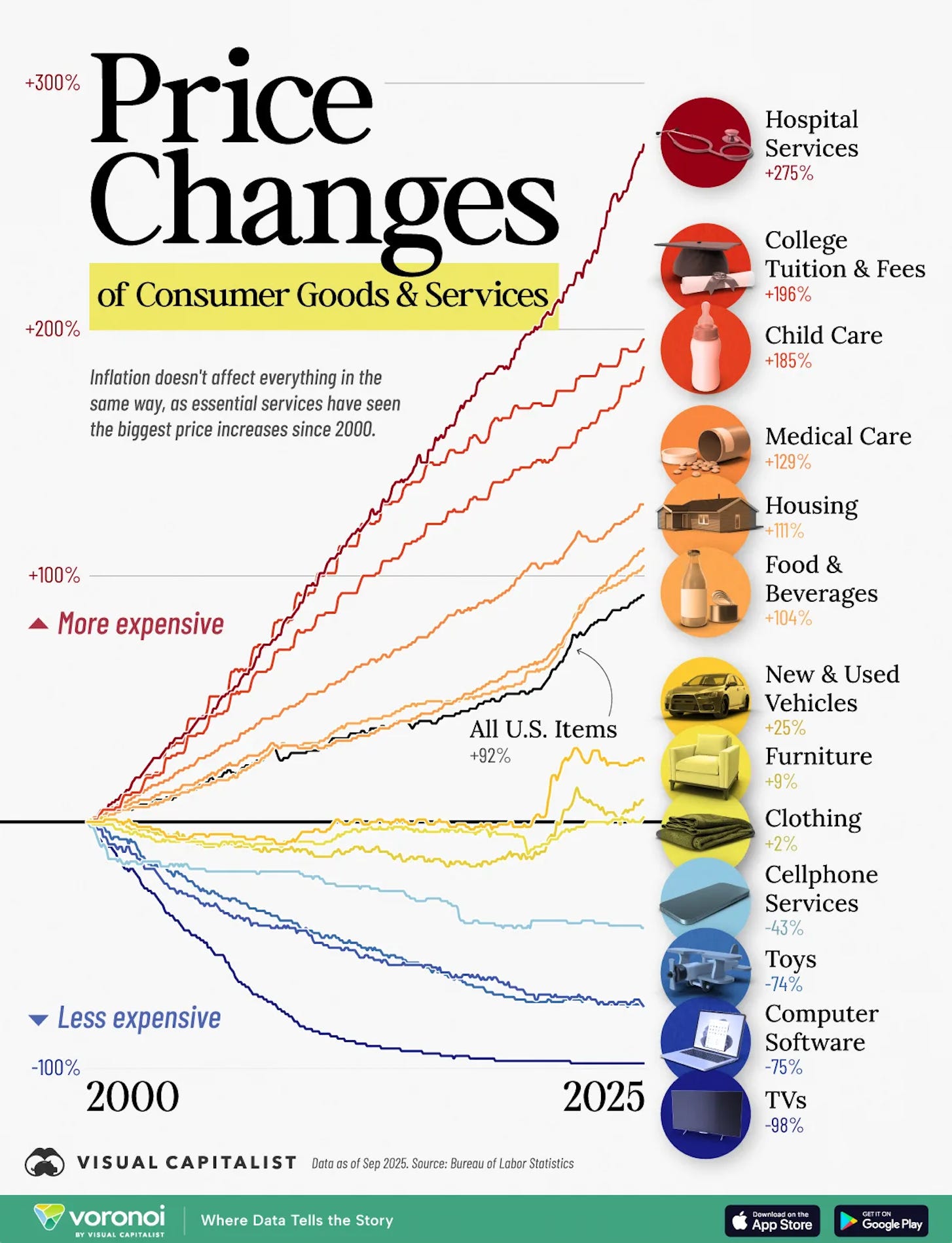

US Inflation - A Tale of Fire and Ice, with the Fire Roaring since 2000 - Overall U.S. inflation has increased 92% over the past 25 years. The cost of many essentials, like hospital services, childcare, medical care, housing, and even the cost of food, are rising at a faster rate than inflation overall. Meanwhile, the cost of technology (software, TVs, toys) is generally becoming cheaper on a relative basis. Hospital services have consistently outpaced inflation over the past several decades, with costs rising a stunning 275% since 2000. For perspective, hospital services increased 6.9% annually as of June 2024, faster than nursing homes (6%), prescription drugs (2.4%), and overall inflation (3%). Today, nearly one in five dollars spent in the U.S. economy goes toward health care, up from one in 20 in 1960. More broadly, prices for essential services have significantly outpaced overall inflation, fueled by consolidation and labor-intensive operations. College tuition and fees have also skyrocketed, rising 196% since 2000. Driving up costs are the hiring of more faculty and increased spending to attract students. Additionally, state funding has seen a long-term downtrend, meaning that colleges must rely more on tuition. As we can see, housing inflation has jumped 111% compared to a 92% increase for all U.S. items. When interest rates hovered near 0% in 2020, it turbocharged housing demand, leading prices to spike to multiple record highs, even as interest rates increased. On the other hand, software has seen a clear deflationary trend, driven by the rise of cloud computing and subscription models. Furthermore, TV prices are 98% cheaper than they were at the turn of the century, thanks to technological advancements and rising manufacturing efficiency.

Learn more: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/chart-inflation-hit-the-hardest-by-category-2000-2025/?mc_cid=7185d6ed4b&mc_eid=814179b7ef

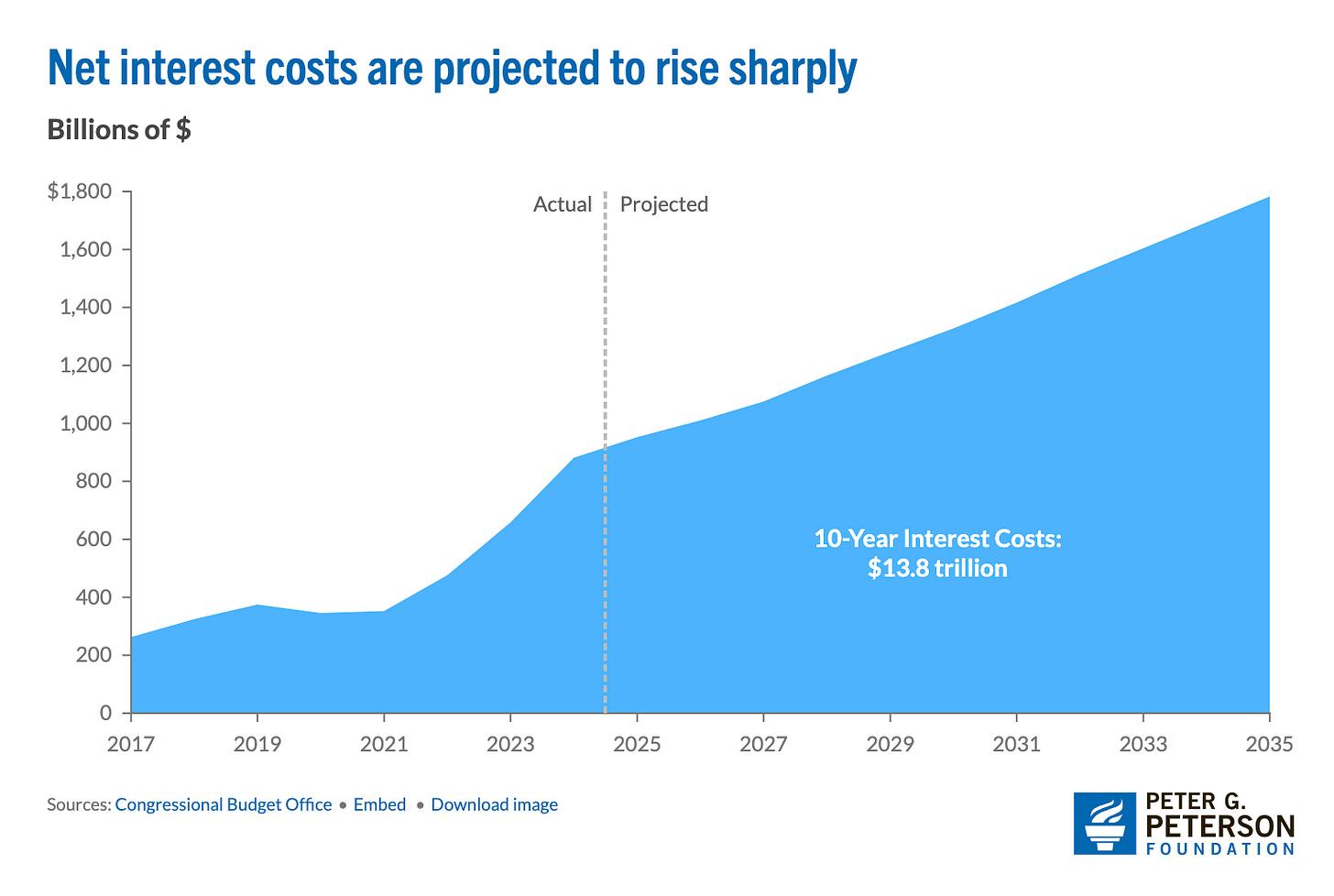

Signal - When your interest on your debt becomes one of your largest expenses you are not in a good place (and your fiscal and monetary policy becomes one which is a tried and tested path to currency debasement) - US interest payments are projected to be the fastest growing portion of the federal budget in upcoming years. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that if current laws generally remain the same, net interest payments will total $13.8 trillion over the next decade, rising from an annual cost of $1.0 trillion in 2026 to $1.8 trillion in 2035.FY2025: Interest payments were about $970 billion, roughly 3.2% of GDP and around 13.8% to 19% of total federal outlays, depending on the source and exact period. FY2026 (Early): Interest costs continue to rise, with some reports indicating they’ve briefly surpassed Medicare and defense spending, becoming the #2 expense.

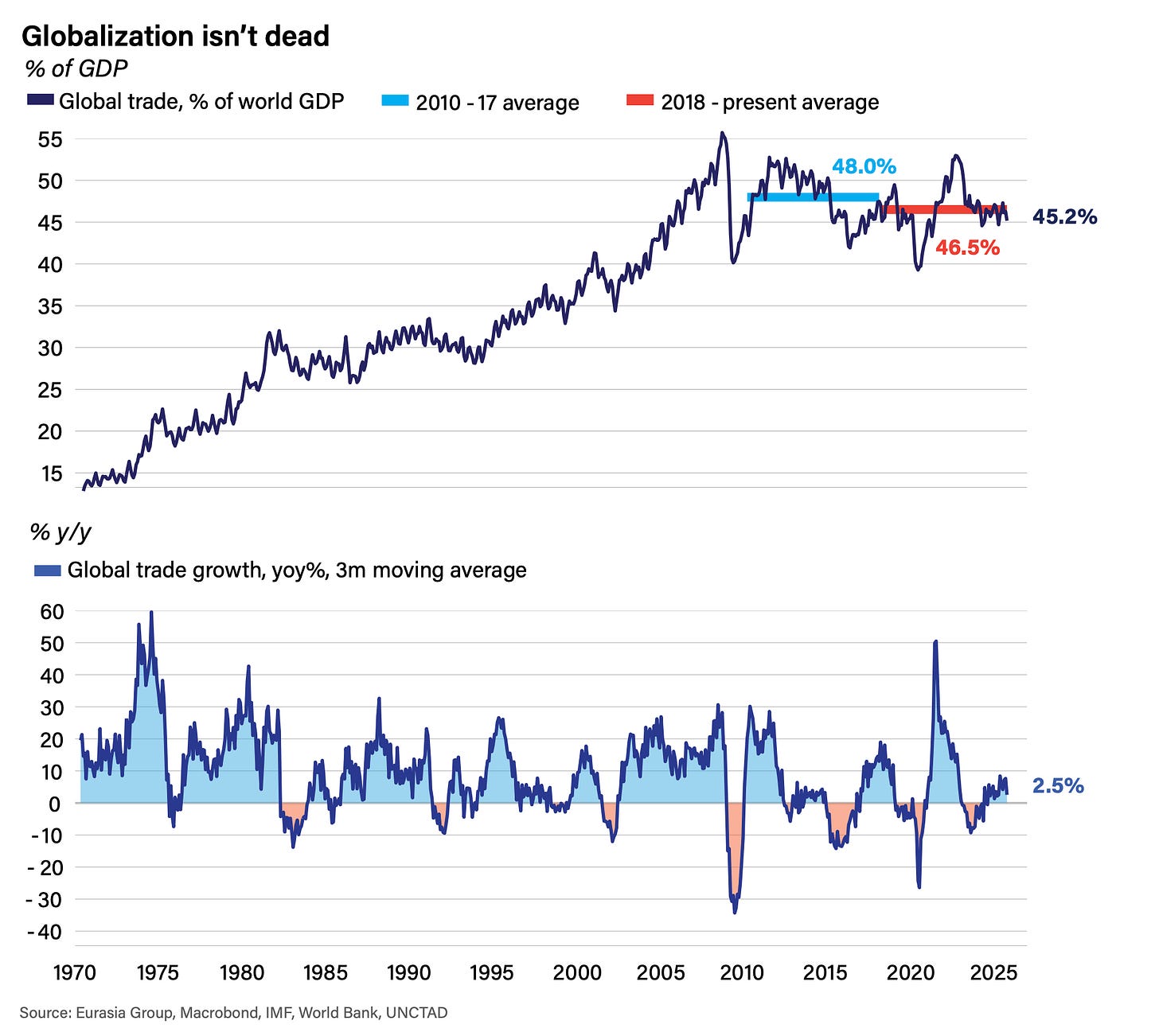

The Path we are on…Globalization’s demise has been greatly exaggerated - trade, finances and ideas still flow, they have just been reconfigured…

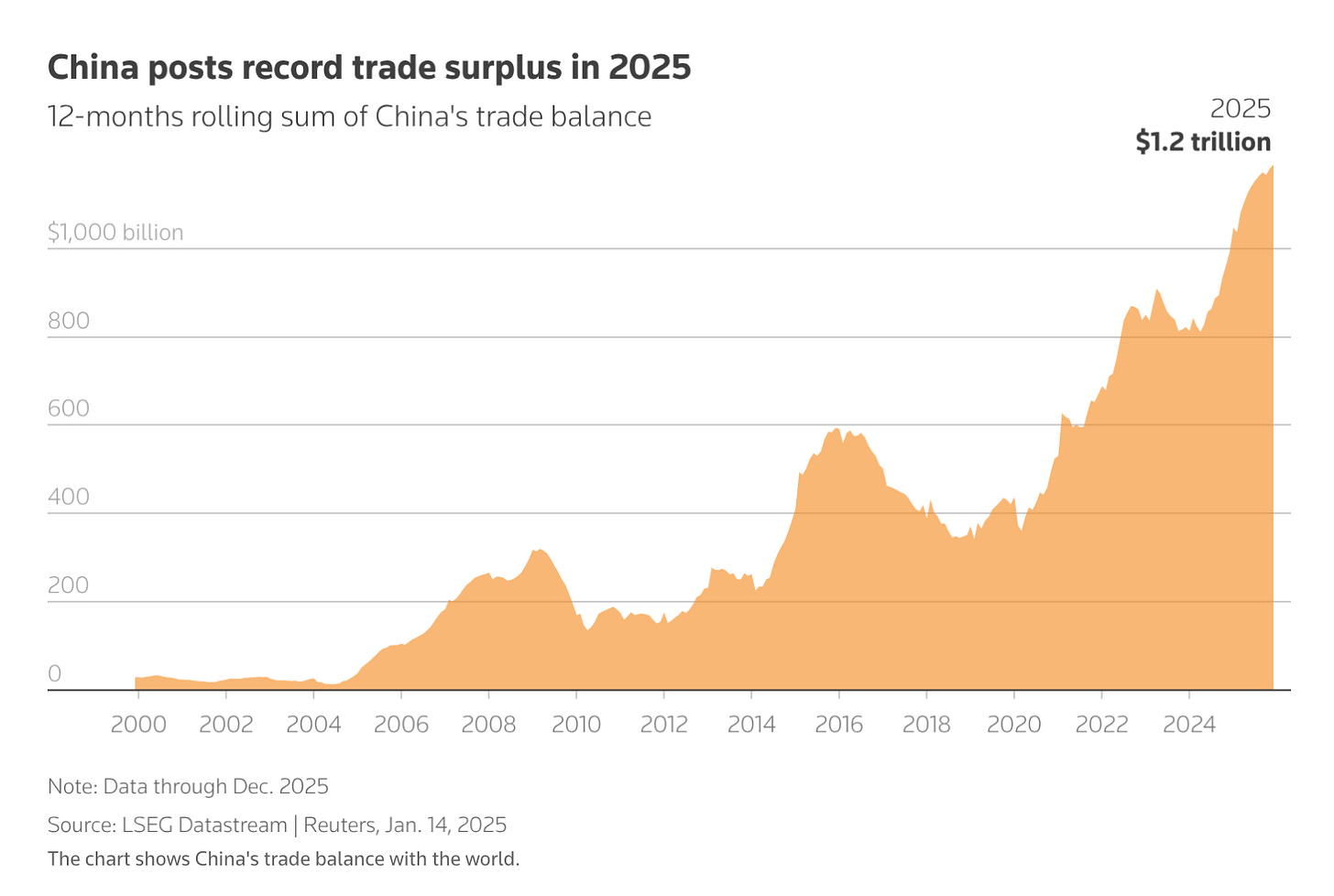

The politics are noisy and bombastic, but the reality is harder to change - “China on Wednesday reported a record trade surplus of nearly $1.2 trillion in 2025, led by booming exports to non-U.S. markets as producers looked to build global scale to fend off sustained pressure from the Trump administration. The Asian powerhouse economy’s monthly trade surpluses exceeded $100 billion seven times last year. A push by policymakers for Chinese firms to diversify beyond the world’s top consumer market by shifting focus to Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America paid dividends, cushioning the economy against U.S. tariffs and intensifying trade, technology and geopolitical frictions since President Donald Trump returned to the White House last year.”

Learn more: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-trade-ends-2025-with-record-trillion-dollar-surplus-despite-trump-tariffs-2026-01-14/

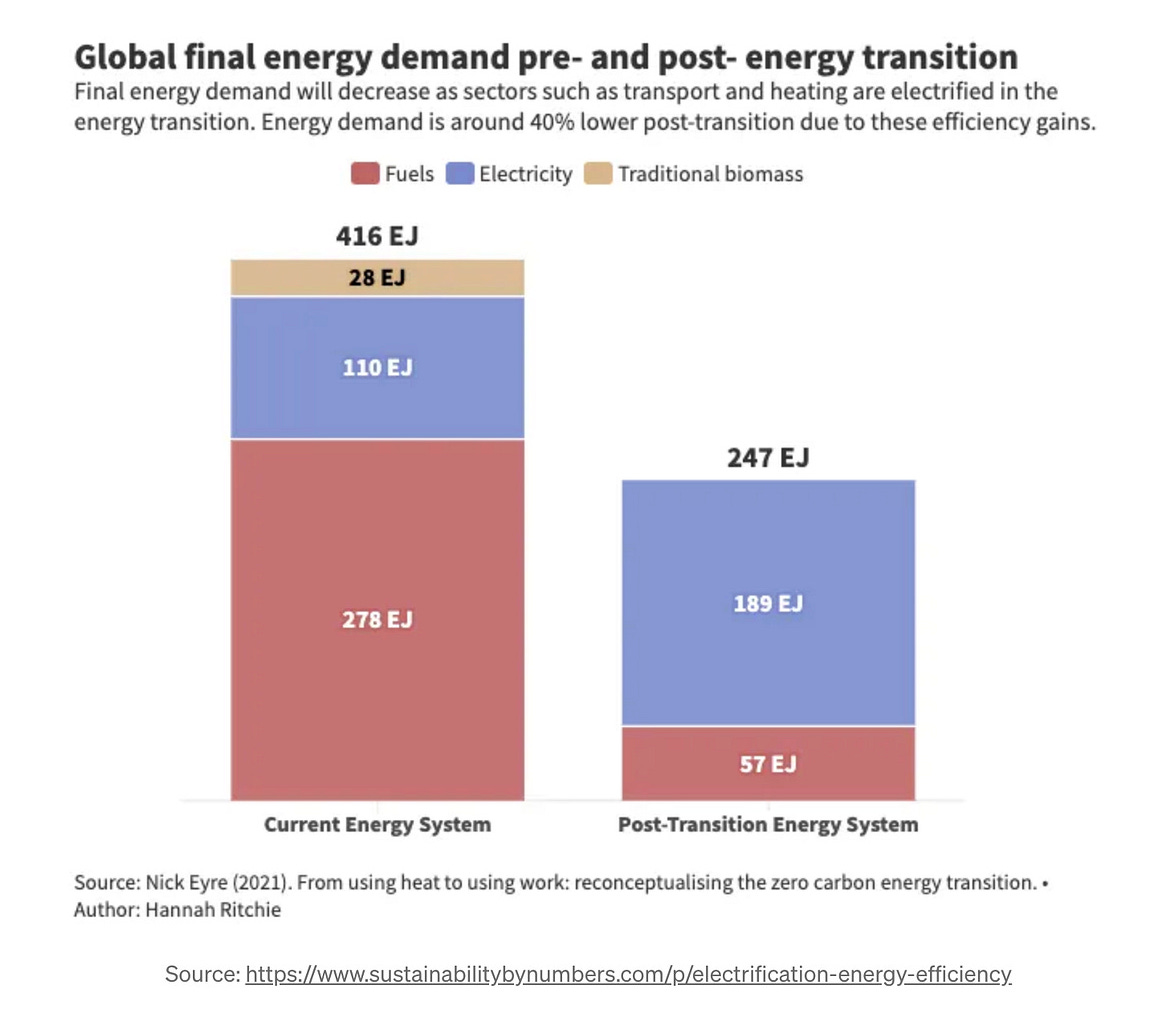

Riding Wright’s Law down Electric Avenue - “Electrification is efficiency - When we electrify our energy systems, a magical thing happens: large inefficiencies vanish. As the International Energy Agency puts it: “Electrification is efficiency”. In a decarbonised world, our final energy demand is much lower than it is today. A study by the Oxford Professor Nick Eyre suggests it’s about 40% lower. This is shown in the chart below. It plots global final energy demand today compared to a ‘post-transition’ energy system where suitable sectors are electrified, and the rest is fuelled by hydrogen. Electricity demand does increase – from 110 to 189 EJ, but total energy demand drops from 416 to 247 exajoules (EJ).”

Learn more:

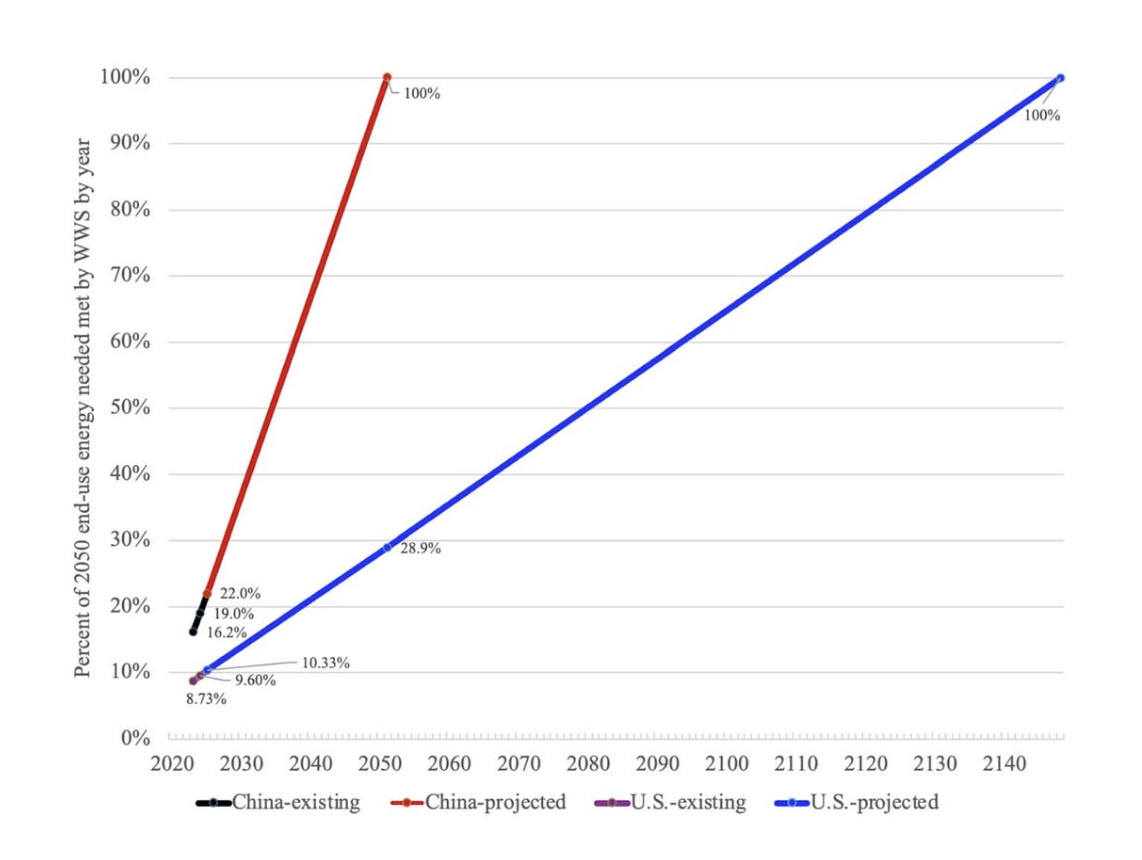

Getting Electric - Renewable gap ↑ At today’s build rates, China is on track to reach 100% renewables by 2051. The US by 2148 unless it solves permitting, grid build-out and siting. Battery build-out ↑ Also, China commissioned more than 65 GWh of grid-scale battery storage in December alone – over 15 GWh more than the US added in all of 2025.

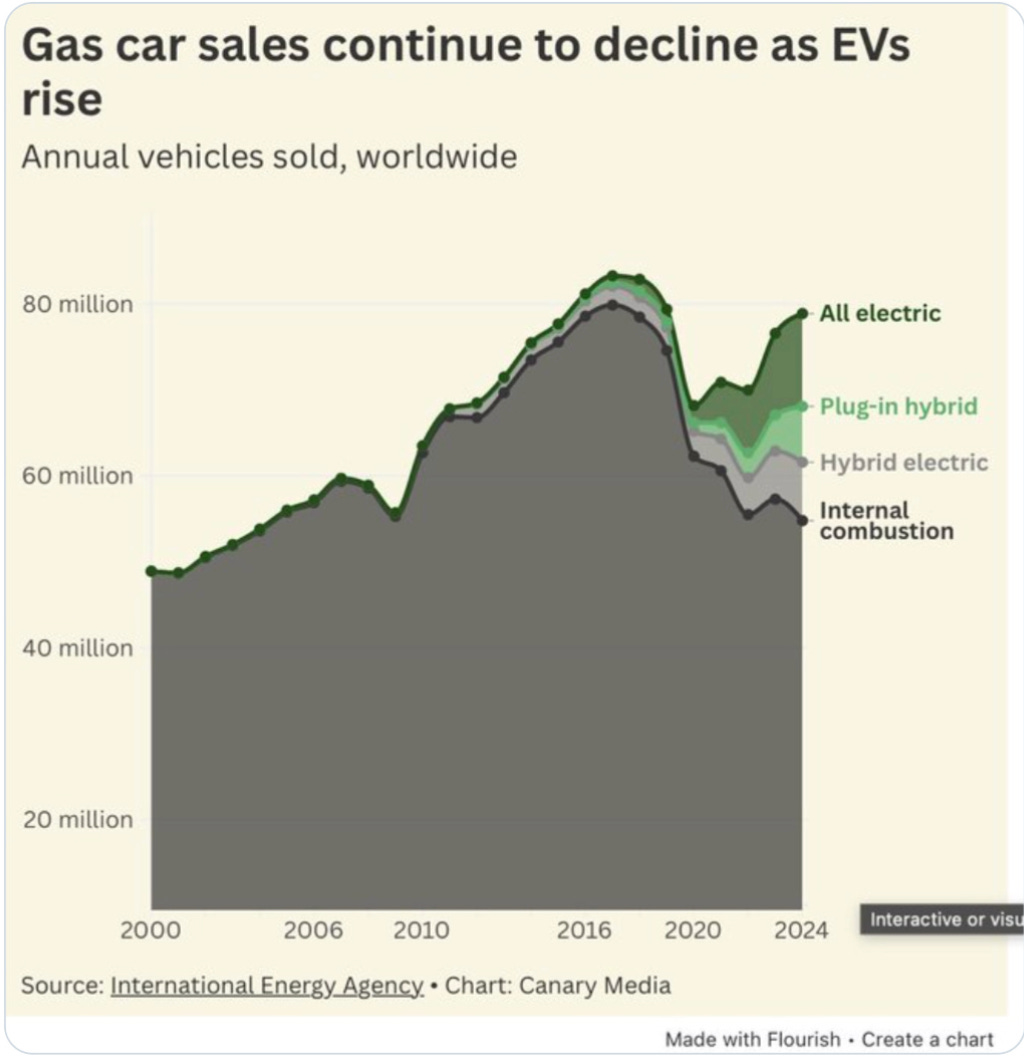

A Tipping Point in Global Transportation - Internal combustion vehicles sales in permanent decline…

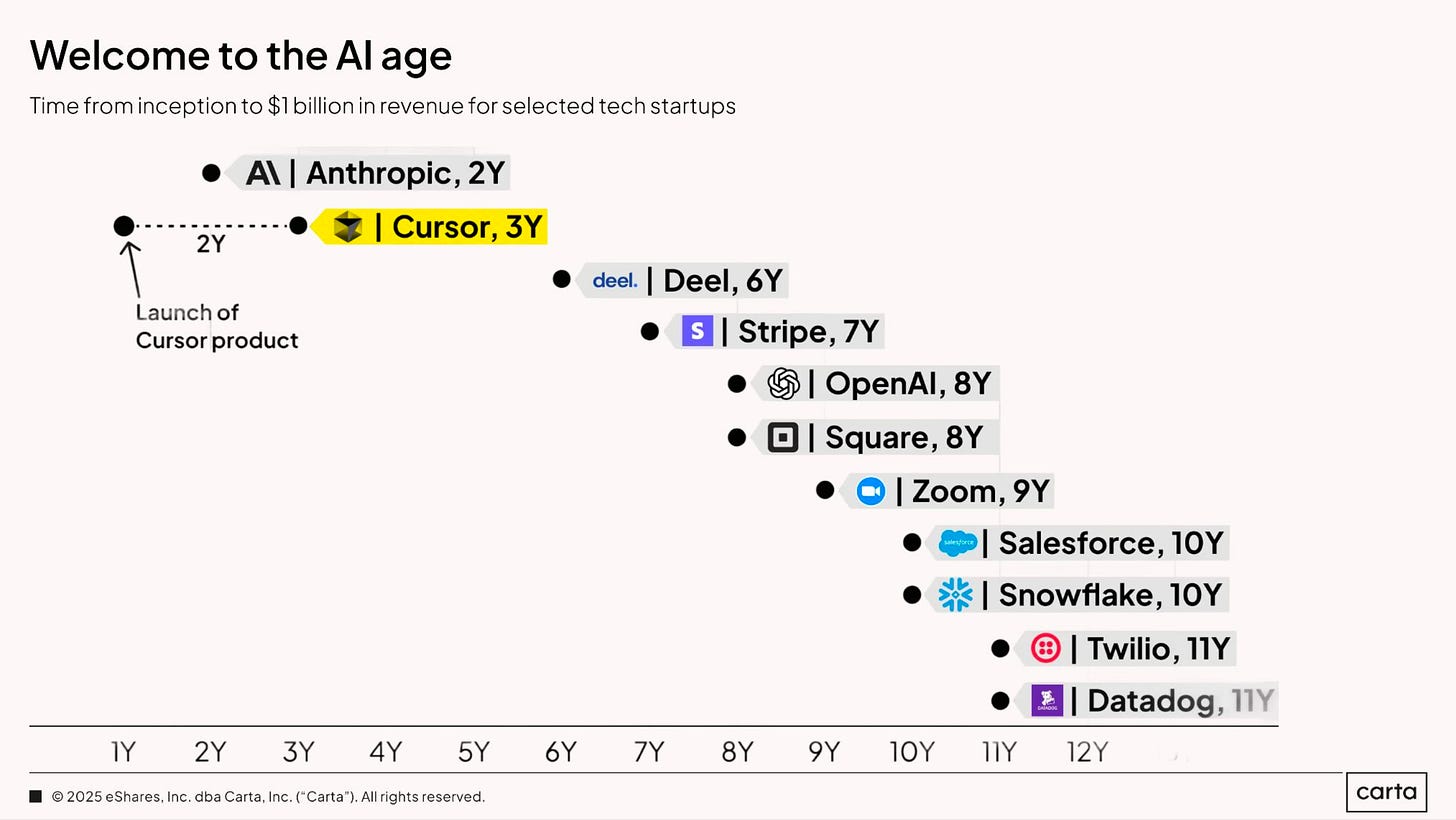

Welcome to the AI Age - Land of the Revenue Unicorns…Time from inception to $1bln in revenue for Tech startups collapses…

2 If You Read One Thing Today - Make Sure it is This

Jacob Rintamaki takes a deep dive into robotics and automation AKA “The Final Offshoring” - Understanding this key input into a key General Purpose Technology leap that is already affecting multiple major industries is important for mapping out the potential paths ahead…Go ponder it here in full:

https://finaloffshoring.com/The_Final_Offshoring.pdf?utm_

Some Takeaways

Why Robotics Will Work

If you try to look to the past to understand the future of robotics, then the future is bleak.

Dancing humanoids may crowd the trade show halls of Shenzhen but factory floors are still conspicuously empty. Most robot companies that have not gone bankrupt have stayed confined to household appliances, narrow industrial automation, or “boxes with wheels,” whether iRobot with its Roomba, Locus with their warehouse AMRs, or, more recently, Waymo with its self-driving cars.

Thus, why should the future be any different? Why should one expect a sudden, dramatic wave of robotics working not just in the coming decade, but the coming handful of years? Why should the curse of Moravec’s Paradox suddenly break?

The standard answer a savvy technologist would give is that increasingly capable AI video and world models will serve as a “base,” providing real-world understanding, while deployments, whether through teleoperation, data gloves, or egocentric capture, will generate an additional data flywheel. This has already led to interesting emergent behaviors: absorbing egocentric data, tactile sensing, and generalization across environments. And we’re about to scale everything up by 100x. Long robotics. Things will be big soon.

I think this is mostly correct, but let me add some nuance around both why to be bullish and two of the challenges that robotics faces today.

The Nuanced Bull Case

First, robot deployment is valuable even beyond just being a data flywheel for robotics models. For one, it seems like real-world data on your specific robot embodiment is the best kind of data to collect. But, in addition to that, the increased ability of Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models to “absorb” egocentric data is directly related to how much diverse robot data the model was trained on. So, every time we deploy a robot, it can now be “amplified” by egocentric data. Furthermore, as we deploy more robots, the industry will gain morale, a lower cost of capital from creditors, and a better understanding of how to solve real problems for real customers, rather than just being stuck in a lab forever.

Second, I think most still don’t realize how unoptimized everything is in robotics compared to what it could be. For the longest time, robotics’ core problem was its lack of data, which needed ALOHA, UMI, and Diffusion Policy to break the chains. However, now that we are able to stably train on and acquire increasingly large quantities of data, we can start changing many layers of the stack, from pretraining to teleoperation systems to even trying to hyperoptimize robotics via speedruns, similar to LLM speedruns such as NanoGPT.

This lack of optimization is why there are so many different approaches to robotics at the technical level, from simulation-focused companies to those focused on diverse data to those focused on multiple real-world embodiments and techniques. It’s also why the “robotics foundational model” layer is more contested than one would expect, which is why many are becoming “full-stack” competitors, as we’ll later describe.

Third, robots do not need to be perfect initially to have a big enough economic impact to keep the “hype flywheel” spinning. As we’ll discuss in the markets section, one framing of general-purpose robotics that I haven’t seen much of isn’t that we now have a robot that can do anything, but rather we have a robot which can quickly, cheaply, and easily be made to do one thing very well. If you think about the size of the TAM in jobs involving narrow, repetitive labor then, well, there you go.

There’s your flywheel.Challenges

First, “evals” for robots are very primitive compared to LLMs. As Kyle Vedder of Physical Intelligence put it, “LLMs differ from robotics. . . LLMs are able to be rolled out an unlimited number of times from the identical state s. [Robots, by comparison, cannot be rolled out an unlimited number of times from the identical states.]”

Furthermore, unlike the Kaplan or Chinchilla scaling laws, robotics has to deal with different embodiments, environments, tasks, and other small nuances which make extracting a single “log-linear curve of destiny” quite difficult. However, I believe much of this is also due to the relatively primitive state of robotics and world models, at least compared to where it will be in the near future. Furthermore, LLM evals will also need to be updated to account for progress. For example, METR’s long-horizon tasks evals might need to switch to measuring “human programming uplift,”as ex-OpenAI researcher Daniel Kokotajlo proposes in the depths of the AI Futures Project’s new forecasting model. Similarly, robotics will also need evals that measure long-horizon capabilities, in addition to generalization, which is described as being both “faked” in many companies’ demos and the source of controversy over whether “fine-tuning” is general enough.

Second, I believe that the speed at which robots do tasks is asymmetrically important for the rest of the world. While an astute observer would note that the core problem with robotics has always been generalization, not speed, it does seem “quite lame” to have all robot demonstrations on 4x or 10x speed. However, we’ve already advanced far beyond naive speedups into SpeedTuning, SpeedAug, advantage-conditioned RL, and training on “real-speed” data rather than slow teleoperated data. I suspect a non-trivial portion of many people’s skepticism will be washed away as “1x speed” demonstrations are increasingly shown; it certainly has for me.”

“…underestimating China would be a very grave mistake, and I don’t want to be perceived as flippant here. To start, even large infusions of capital cannot easily replicate the highly competitive, deeply networked ecosystems which make up the Chinese robotics and broader manufacturing ecosystem. Secondly, while there have been backdoors which have been found in companies such as Unitree, many are still using these robots because there are no realistic alternatives at the moment to use. Granted, Unitree is mostly used for entertainment purposes rather than industrial ones, but it should be concerning that there are hardly any “buy now” buttons for most non-Chinese robotics companies.”

“Furthermore, if you trace the robotics stack from the top down, from the finished humanoid to the raw inputs, you will notice that minerals are upstream of almost everything. The robot needs actuators. Actuators need motors. Motors need magnets. And magnets need rare earths.

China controls roughly 85% of global rare earth processing and 90% of rare earth magnet production, and has already begun to impose export controls. While, yes, the geographical distribution of rare earths is fairly abundant, the processing capabilities are not, and one can just look to Standard Oil to understand how important monopolizing processing capabilities before taking over the entire “stack” can be for a company or nation.”

“The real worry, to me, is more so in actuators, which is really a problem of precision reducers.A precision reducer is a mechanical device that sits between a motor and a joint. The motor spins super fast but with a low torque, which the reducer then converts into a slow, precise motion. The two main types are harmonic drives, which use a flexible gear that deforms inside a rigid outer gear, and RV reducers, which use a planetary gear system. But both require manufacturing precision measured in microns.

And that’s where the trouble starts.

The Japanese conglomerates Harmonic Drive and Nabtesco dominate this market. Nabtesco alone holds 60% of the global market for RV reducers. These components are difficult to replace or scale because certain failure modes only emerge after thousands of hours of operation. Tribology, the study of friction and wear between interacting surfaces, is devilishly complex. The knowledge is empirical and accumulates slowly.”

“…Chinese manufacturers are catching up. Green Harmonic, Leaderdrive, Zhongda Leader, Shuanghuan Transmission. They are shipping reducers at 80 to 90 percent of Japanese quality for 30 to 40 percent of the price. This matters not because American companies will necessarily use Chinese reducers but rather because of the “four-minute mile effect.”

Once the barrier is broken, everyone knows it can be done.

China has proven that cheap, good-enough reducers can be manufactured at scale. Which means factories in Vietnam and Malaysia can follow, as the ecosystems in Bac Ninh and Penang are deeply underrated.”

The Cost of Robots

The implication from this is that robots will cost closer to an iPhone than to a car.There are a few ways you can arrive at my conclusion. The first is simply just by looking at the size of a robot (which could be just arms, or just arms and a wheeled base) versus a car. Why would a normal robot, which is made out of much less raw materials and does not need to be safety qualified the same way a vehicle which could move over 100 mph is, cost the same from a hardware OEM standpoint?

The second is that “robots making robots,” which is often dismissed as a “sci-fi” or “deus ex machina” explanation for why the cost of producing robots could collapse, is not as science fiction of a concept as it sounds. FANUC has been doing this, albeit in a much, much narrower way, since 2001. As robots get more general, we can just gradually expand what FANUC has been doing for 25 years now.

However, regardless of how you reach this conclusion, it’s quite important because it will shrink the payback time for robots down by quite a bit. This, after default risk, is a major thing that creditors look for, and if an increasing amount of credit can be poured into robotics, then it could kick off many, many flywheels for the industry.”

“If you’re like me, you just read the previous section and are now quite bullish on robotics happening. However, before we get into the much more speculative side of things, I think that it is important to understand what the markets for robotics will look like.

I believe this is important because there are likely many interesting information asymmetries to be found here with careful analysis.

A high quality view of the markets in robotics can be found in “The 2026 AI Forecast with Sarah & Elad”. Their viewpoints can be roughly blended in with what is my understanding of smart venture investors’ perspectives on robotics as the following: Incumbents are favored because robotics will be capital-intensive and require hardware/supply chain expertise. Yes, Tesla, SpaceX, and Anduril were able to pull it off, but those were abnormal startups. Granted, there will still be startups that do well here, but incumbents like Tesla and the Chinese companies will be very strong. Additionally, there’s a lot of uncertainty around how the market will shape up, but it seems like there will be markets around data collection, horizontal software, enterprise robotics, home robots, hardware OEMs, and robotics model providers.

Personally, I think this seems to be mostly correct, but there are a lot of details we could layer in here. We’ll first address some of the “macro variables” that could affect these markets, and then address enterprise robots, hardware OEMs, robotics model providers, data collection/horizontal software, and home robots. “Robot specific” markets which will emerge over time will be addressed in later sections.”

“…credit will play a larger role in robotics than they do for traditional tech startups because robotics has an industrials component which B2B SaaS doesn’t. So, the key variable for companies to focus on will be “payback times,” in addition to “what is the equity multiple over ̃3-5 years once you leverage your asset pools?” RaaS-based financing from domain experts will also become increasingly valuable compared to taking on traditional private credit or venture debt. But, interestingly enough, private equity (such as EQT and 1X’s deal) will have a mutually symbiotic relationship with robotics companies, not just because many PE funds also run massive private credit businesses and venture arms, but because robotics can improve the performance of their portfolio companies.

Thirdly, Asia will not just manufacture robots; they will also buy robots. Many might dismiss Asia as a market because of their lower cost of labor, but rising elderly populations, AI datacenter booms causing demand increases, rising labor costs, population decline, fertility decline, government policies, and a high density of manufacturing robot deployment all point towards the markets here being unusually interesting.

And then there is the policy tailwind, because The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA) includes 100% bonus depreciation for qualifying equipment.

It means that you can depreciate the entire cost of a relevant piece of equipment in year one instead of spreading it over five to seven years.

Both robots and AI infrastructure qualify. And there is no cap.

Off to the races!

“The strategy for these companies then, given that reducing payback time may be All You Need, is to deploy into large enterprise customers as aggressively as possible to start building moats that their larger video/world-model focused competitors still find difficult to match, similar to the best AI Application layer companies. This is also similar to the strategy which have made the “systems integrator” companies, a la ABB, Siemens, FANUC, KUKA, and so on, remarkably durable: deploy, deploy, deploy into customers, and become their go-to person for fixing messy problems.

Within the “enterprise,” of course, there are many potential markets to go after. As just a shortlist: Logistics, Healthcare, Retail, Agriculture, Cleaning, Hospitality, Manufacturing, and Restaurants.

However, the most interesting and underdiscussed set of markets for enterprise “MVR” companies would be anything related to the AI datacenter buildout.”

The Future Is Not Fixed

Now, before we get into more speculative territory, I want to be clear about something: we still have agency over what kind of world we’re building. The future isn’t fixed, and you shouldn’t act like it is.

I bring this up because of a debate that’s been raging in AI’s circles recently. The gist is podcaster Dwarkesh Patel and Stanford economist Philip Trammell recently argued that, in a world where AI and robotics make capital a perfect substitute for labor, inequality will skyrocket and traditional policy tools won’t be able to easily fix it.

Unsurprisingly, this caused a lot of discourse.

Here are my takeaways from all of this:

First, inequality will matter more in a world with abundant robotics and AI. In particular, the inequality of power, not just wealth, will matter, and the developing world could become unusually volatile. Yet, if we’re not in a “crazy world” where the rules of economics are violated, then these problems can be approached with traditional tools: public policy, differential technology development, and the like.

Second, if we are in a crazy world where capital perfectly substitutes for labor, then assuming traditional tools will still work is delusional. When COVID hit, America went from a normally functioning economy to shutting down the NBA and New York City within weeks, appropriating trillions for stimulus checks and PPE production. Now, imagine if something 10x/100x/1000x more important than COVID hit. Why would anyone assume that the reaction would or should be muted and typical?

Personally, however, I believe we’ll be in the “normal” world for the foreseeable future. This will still involve an extraordinary amount of change occurring by historical standards, but not one where the fundamental rules of economics completely break down.

So with that: welcome, one and all, to the final offshoring.”

The Final Offshoring

If you could only say one word about what the final offshoring will bring, it would be this: deflation.If you make labor cheap and abundant, then, for industries which are not heavily regulated, it should deflate the costs of those industries.

The downstream implications of this are enormous.

We’ll start with the Fed, which has the twin mandates of maintaining a 2% inflation rate and maximum employment. The maximum employment point, as tangentially mentioned by Ben Thompson, could be changed by a number of degrees (i.e. “Is podcasting a real job?”), and unemployment is such a catch all term that I don’t think anything about that portion of the Fed would need to be changed because of the final offshoring. However, the 2% inflation target is something to watch out for.

Typically, deflation is fine because it only affects one industry, so consumer spending can be reallocated to other industries. But if there’s a continual broad deflation across the economy, then things could get weird.

The Fed tends to fight deflation by cutting interest rates, but you cannot cut interest rates meaningfully below zero. Both Europe and Japan tried negative rates with mixed results at best. I’m optimistic though, as through a combination of evaluations and methodology updates, the Fed, the BLS, and a variety of other bodies could be better prepared to account for economic changes in an uncertain world.

However, assuming the Fed is fine (which it should be), the impact of deflation on ordinary Americans will be immense. We’ll get into the (many) positive implications shortly, but the core challenge here will be that many jobs that are today worked by people will be impacted, because American jobs tend to have higher wages than jobs overseas. The people who are no longer working those jobs will rightfully have opinions about that!

Satya Nadella once said that “the true cost of energy is social permission.” I think this will be the same for robotics, in that, if the American people are not given a compelling vision of the future that includes them, why would they go along with this?

We’ll cover what happens internationally if we don’t go forward with robotics (spoiler: it’s bad), but I think there is a lot of worry from many Americans about everything turning “socialist” if large wealth, robot, land, VAT, or other taxes are immediately imposed on them. As conditions change, I think a variety of reasonable taxes will be passed under spending bills, but the first set of changes that could be done would be finding a way to work the leading robotics companies into a sort of American Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). Lutnick and Bessent have already discussed doing something like this, and it is quite popular in the American states (notably Alaska with its oil fund) and countries (Norway) where it’s been tried. Who doesn’t love free money (as well as orienting all of our incentives towards growth, rather than division)?”

“Speaking of stability, remember how I mentioned what would happen if we didn’t go forward with robotics? It’s time to talk about that now. If America forfeits being a global player in robotics, then, yes, China will likely surge to be the leader. However, the more worrying perspective is that countries which heavily rely on remittance payments, such as Bangladesh, will suffer as robots replace workers in wealthy countries. Those displaced workers, now with a much weaker case for immigration, will go back to their home countries, which may also be implementing robotic automation, causing currency debasement and possible debt defaults. When that happens, the instability of the world will dramatically increase, particularly since many of the countries most vulnerable to remittance going away tend not to have pre-existing strong democratic institutions which can maintain stability in transitional periods. But, again, if the US can remain at the frontier in robotics, we can serve as a helping hand here.”

“Classically, the four factors of production were land, labor, entrepreneurship, and capital. As labor becomes commoditized, each of the other three factors will change in strange and unexpected ways.”

Land

Land will become more important in the world of the final offshoring. That should be obvious, but how so isn’t.”

“From a consumer perspective, places that are pleasant to live become more valuable. Europe, with its walkable cities and moderate climate and historical depth, is more attractive than ever. In a world of synthetic abundance, authenticity appreciates.

From an enterprise perspective, energy-rich and lightly-regulated land becomes critical, leading to countries with abundant energy potential to become the new centers of industrial power.”

“…we’ll take a page from Tyler Cowen’s book and play a game called “overrated/underrated.”

Overrated: labor-intensive services that cannot differentiate on human presence, traditional manufacturing that fails to adapt, commercial (but not residential) real estate designed for human workers.

Underrated: energy, materials, land, IP-heavy businesses, robotics infrastructure, and whatever else becomes scarce when physical labor is abundant.”

3 Consequential Thinking about Consequential Matters

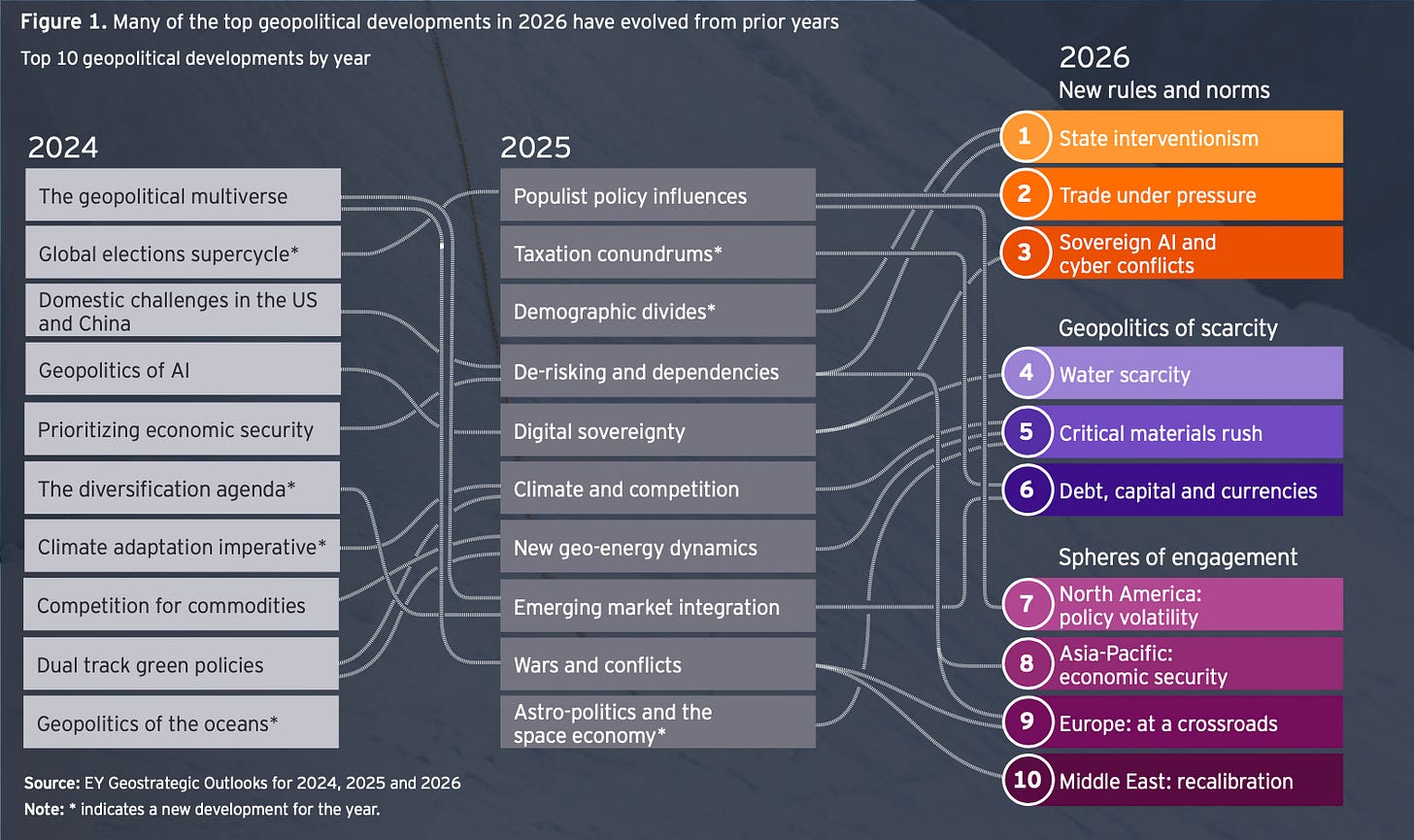

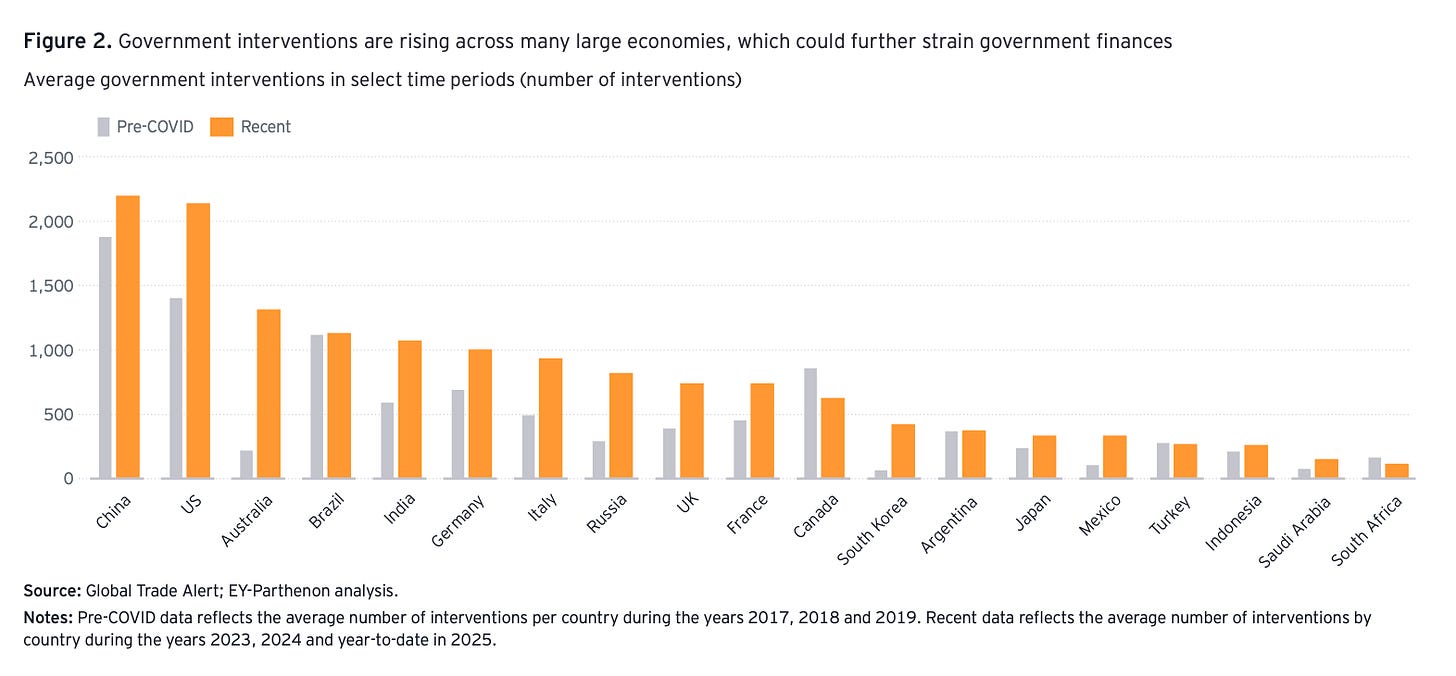

EY shares some perspectives on what they perceive to be the geopolitical realities for 2026 and suggests strategies for navigating them here - It’s a good place to start as you map your own thoughts on these consequential matters…

https://www.ey.com/content/dam/ey-unified-site/ey-com/en-ch/noindex/ey-geostrategic-oulook-2026.pdf?mkt_tok=NTIwLVJYUC0wMDMAAAGfUPTdNtb56f_Th0sSR4_m294hCPykdLMPq89iWf9qbbWA4iYTNPcQpnZAfuyoazhAwGbK6QUsiyJ1sMWXQ292boblbP3L9urH0yahBtg11p69xkrgE3a5

Some Takeaways

State interventionism

Global crises from the 2008 financial crash to the COVID-19 pandemic and Europe’s energy shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushed many countries to move away from free-market orthodoxy and embrace greater state interventionism. Once extraordinary measures for many countries are now hardening into more structural state interventionism, in which governments use industrial subsidies, restrictive trade policies, ownership stakes in companies and local investment mandates to direct economic activity. In 2026, state interventionism will flourish, with differences shaped by domestic fiscal pressures, political dynamics and institutional capacity.”

Trade under pressure

Related to state interventionism, governments have increasingly mandated or incentivized companies to modify existing supply chains and trade patterns. Policy choices by the US and China to reduce trade deficits or maintain surpluses mean that the world’s two largest economies will continue to be the source of much of this trade system rebalancing. In 2026, tariffs, export controls and local content requirements will continue to pose supply chain challenges — although efforts to secure new trading blocs may offer limited opportunities.”

“A partial counterbalance to these trends will be smaller groupings of countries pursuing trade liberalization without the US or China. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) brought on the UK as a new member in 2025 and more countries are seeking admission. The

EU and Mercosur concluded their FTA after 25 years of negotiations — although ratification is not yet assured. These developments point to a “friendshoring” or “mini-lateralism” trade system that will start to emerge, in which governments around the world engage in new or expanded bilateral, regional or plurilateral trade agreements.”

Sovereign AI and cyber conflicts

Digital and cyber conflicts have surged in recent years, driven by escalating geopolitical tensions and intensifying competition over control of critical technologies. In response, governments have expanded digital sovereignty measures, with a focus on their domestic AI systems and the hardware and software that power them. Despite these efforts, gaps in sovereignty continue to present risks for cyber operations and for countering hybrid tactics aimed at disrupting critical infrastructure and acquiring sensitive IP. In 2026, AI will serve as a force multiplier of cyber conflicts, as it continues to be the primary technology of geopolitical competition.”

Water scarcity

Nearly 4 billion people already experience severe water scarcity for at least one month each year, a figure expected to rise in 2026 due to rising demand and more frequent droughts. While there are many drivers of the trend of growing global water demand, public debate will likely focus on the resource needs of data centers and semiconductor manufacturing — leading to conflicts over water resources both within and between states. In 2026, water rights and usage will both cause and exacerbate political conflicts, leading to trade-offs in resource allocation across industries.”

Critical materials rush

Commodity cycles have become more volatile and intense in recent years, according to the World Bank, driven in part by geopolitical competition and fragmentation as well as the energy transition. Governments are increasingly treating critical minerals — a diverse and growing set of minerals, which

are essential for a range of strategic technologies and sectors — as elements of national power, in terms of both economic competitiveness and national security. In 2026, the race to gain or retain access to critical minerals for digital technologies, high-capacity batteries and defense systems will lead to new production and trade patterns.”

Debt, capital and currencies

The global financial system is entering a more fragile and politically charged phase. Global debt remains above 235% of world GDP, according to the IMF, reflecting only a modest post-pandemic correction. Persistently high borrowing costs are straining both fiscal and financial stability, amplifying sensitivity to interest rate changes and global capital market volatility.

Geopolitical competition and the growing politicization of capital allocation are set to intensify in 2026, reshaping the contours of the global financial system. Governments are continuing to prioritize spending on defense, industrial policy and social protection — even as debt- servicing costs rise faster than any

other major budget category. The OECD expects record-high sovereign bond issuance of nearly $17 trillion in 2025. This fiscal trajectory risks crowding out private investment and keeping long-term rates structurally higher. Fitch Ratings’ downgrade of its 2025 global sovereign outlook to “deteriorating” highlights the growing risk of debt distress, especially among economies with weak institutional credibility or high external financing needs.”

“In the US, this tension is compounded by an increasingly charged debate over Federal Reserve independence. The dollar’s dominance continues to rest on structural foundations such as deep and liquid capital markets and institutional credibility. But even the perception of political interference has contributed to wider risk premia and a reassessment of the dollar’s durability as the world’s anchor currency, with the dollar falling about 10% relative to its 2024 peak. The US dollar still accounts for about 56% of global foreign exchange reserves, according to the IMF, but its share has modestly eroded over the past two decades as global investors diversify toward gold, other currencies and select digital assets to hedge geopolitical risk.”

4 Big Ideas

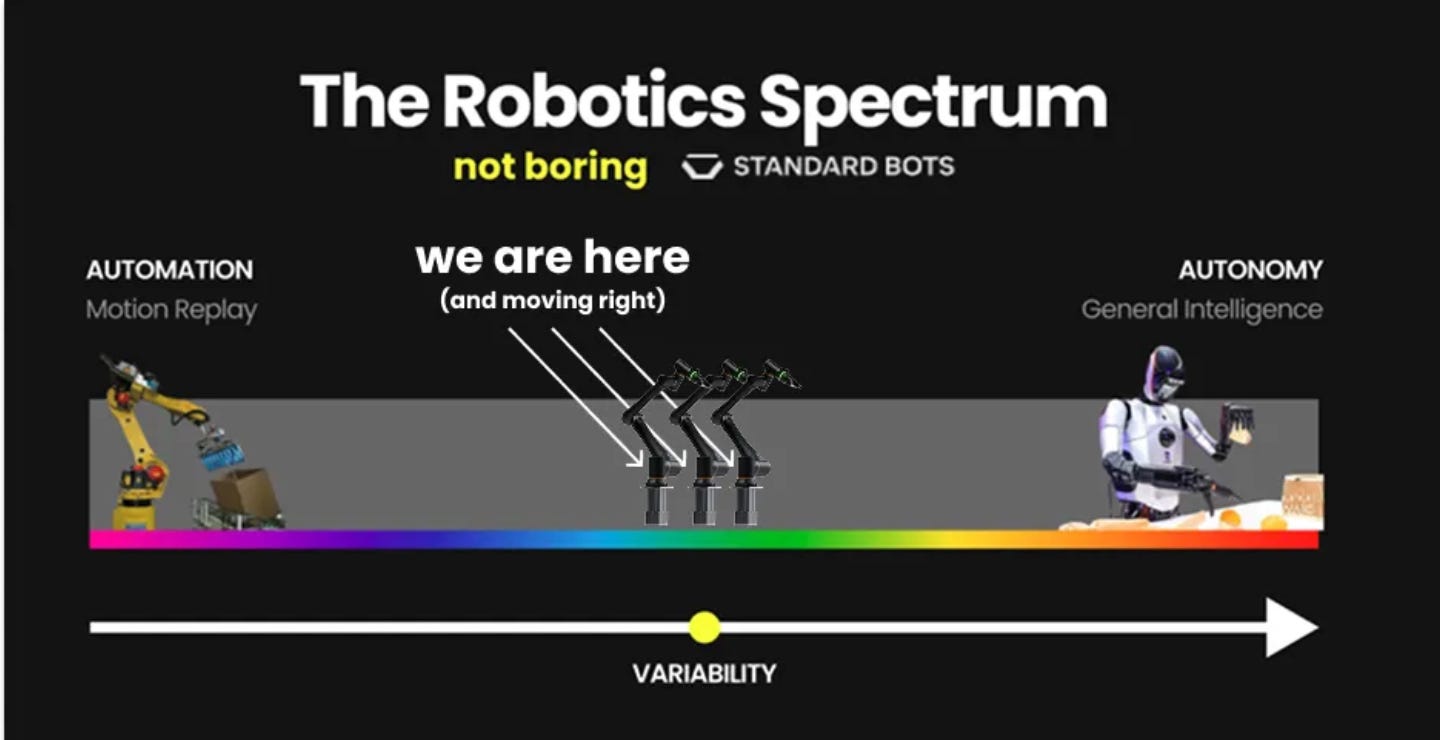

Packy McCormick and Evan Beard (Evan is the founder of https://standardbots.com/ so while he is very transparent and explores pros/cons of different models, he is obviously biased and telling his company’s story - still very informative and worthwhile) takes the “Many Small Steps for Robots, One Giant Leap for Mankind” here - Plenty of Big Ideas on the path ahead for robotics and automation gets explored, go join the journey here in full:

Some Takeaways

“There is a belief in my industry that the value in robotics will be unlocked in giant leaps.

Meaning: robots are not useful today, but throw enough GPUs, models, data, and PhDs at the problem, and you’ll cross some threshold on the other side of which you will meet robots that can walk into any room and do whatever they’re told.

In terms of both dollars and IQ points, this is the predominant view.

I call it the Giant Leap view.The Giant Leap view is sexy. It holds the promise of a totally unbounded market – labor today is a ~$25 trillion market, constrained by the cost and unreliability of humans; if robots become cheap, general, and autonomous, the argument goes that you get Jevons Paradox for labor - available to whichever team of geniuses in a garage produces the big breakthrough first. This is the type of innovation that Silicon Valley loves.

Brilliant minds love opportunities where success is just a brilliant idea away.

The progress made by people who hold these beliefs has been exciting to watch.

Online, you can find videos of robots walking, backflipping, dancing,unpacking groceries, cooking, folding laundry, doing dishes. This is Jetsons stuff. Robotic victory appears, at last, to be a short extension of the trend lines away. On the other side lies fortune, strength, and abundance.

As a result, companies building within this view, whether they’re making models or full robots, have raised the majority of the billions of dollars in venture funding that have gone towards robotics in the past few years. That does not include the cash that Tesla has invested from its own balance sheet into its humanoid, Optimus.”

“To be clear, the progress they’ve made is real.

VLAs (vision-language-action models), diffusion policies, cross-embodiment learning, sim-to-real transfer. All of these advancements have meaningfully expanded what robots can do in controlled settings. In robotics labs around the world, robots are folding clothes, making coffee, doing the dishes, and so much more. Anyone pretending otherwise is either not paying attention or not serious.

It’s only once you start deploying robots outside of the lab that something else becomes obvious: robotics progress is not gated by a single breakthrough.

There is no single fundamental innovation that will suddenly automate the world.

We will eventually automate the world. But my thesis is that progress will happen by climbing the gradient of variability.

Variability is the range of tasks, environments, and edge cases a robot must handle. Aerospace and self-driving use Operational Design Domain (ODD) to formally specify the conditions under which a system can operate. Expanding the ODD is how autonomy matures. It’s even more complex for robotics.

Robotic variables include what you’re handling (identical vs. thousands of different SKUs), where you’re working (climate-controlled warehouse with perfect lighting vs. a construction site with dust, uneven terrain, weather, and changing layouts), how complex a task is (single repetitive motion vs. multi-step assembly requiring tool changes), who’s around (operating in a caged-off cell vs. collaborating alongside workers in shared space), how clear the instructions are (executing pre-programmed routines vs. interpreting natural language commands like “clean this up” or “help me with this”), and what happens when things go wrong (stopping when something goes wrong vs. detecting errors, diagnosing causes, and autonomously recovering).

Multiply these variables together and the range can be immense.

This is because the spectrum of real, human jobs is extremely complex. A quick litmus test is that a single human can’t just do every human job.

Most real jobs are not fully repetitive, but they’re also not fully open-ended.

They have structure, constraints, and inevitable variation, much to the chagrin of Frederick Winslow Taylor, Henry Ford, and leagues of industrialists since. Different parts, slightly bent boxes, inconsistent lighting, worn fixtures, humans nearby doing unpredictable things.

It’s the same for robots.”

“At one end, you have motion replay. The robot moves from Point A to Point B the same way, every time. No intelligence required. This is how the vast majority of industrial robots work today. You save a position, then another, then another, and the robot traces that path forever. It’s like “record Macro” in Excel. It works beautifully as long as nothing ever changes.

At the other extreme, you have something like a McDonald’s worker. Different station every three minutes. Burger, then fries, then register, then cleaning. Totally different tasks, unpredictable sequences, human interaction, chaotic environment. The dream of general physical intelligence is a robot that can walk into this environment and just... work.

At one extreme is automation. At the other is autonomy. Between those extremes lies almost all economically valuable work.”

Play with the interactive robotics spectrum and see real use cases here: https://claude.ai/public/artifacts/bbb099af-26cf-4327-b4e1-f98b28f73d25

“It’s my belief that these small steps across this spectrum are where we’ll unlock major economic value today.”

Two Strategies: Giant Leap or Small Step

If you believe there’s a massive set of economically valuable tasks waiting on the far side of some threshold, then the optimal strategy is to straight-shot it. Lock your team in the lab. Scale models. Scale compute. Don’t get distracted by deployments that might slow you down. Leap.

If you believe, like we do, that there is a continuous spectrum of economically valuable jobs, many of which robots can do today, then the best thing to do is to get your robots in the field early and get to work.

Each deployment teaches you where you are on the gradient. Success shows you what’s stable, failure shows you where the model breaks, and both tell you exactly what to work on fixing next. You iterate. You take small steps.”

“Whenever robotics evolves to incorporate another aspect of the job spectrum between automation and autonomy, it also unlocks another set of jobs, another set of customers, another chunk of the market. One small step at a time.

Take screwdriving. It is much easier to use end-to-end AI to find a screw or bolt than to try to put everything just so in a preplanned and fixed position. Search and feedback is cheap for learning systems. Our robot can move the screwdriver around until it feels that it’s in the right place. It wiggles the screwdriver a little. It feels when it drops into the slot. If it slips, it adjusts. And when our robots figure out how to drive a screw, it unlocks a host of jobs that involve screwdriving. Then we start doing those and learn the specifics of each of them, too.

We learn on the job and get better with time.

Many of these robots are imperfect, but they’re still useful. There’s no magic threshold you have to cross before robots become useful.

That’s not our hypothesis. It’s what the market is telling us.

Industrial robotics is already a large, proven market. FANUC, the world’s leading manufacturer of robotic arms, does on the order of $6 billion in annual revenue. ABB’s robotics division did another $2.4 billion in 2024. Universal Robots, which was acquired by Teradyne in 2015, generates hundreds of millions per year.

These systems work, even though they work in very narrow ways. Companies spend weeks integrating them. Teams hire specialists to program brittle motion sequences. When a task changes, those same specialists come back to reprogram the whole thing, for a fee. The robots repeat the same motions endlessly, and they only work as long as the environment stays exactly the same.

Despite all of that friction, customers keep buying these robots! That’s the market talking. Even limited, inflexible automation creates enough value that entire industries have grown around it. The low-variability left side of the spectrum already supports billions of dollars of business.

In machine learning, progress rarely comes from a single leap. It comes from gradient ascent: making small, consistent improvements guided by feedback from the environment.

That’s how we think about robotics too.

Our plan is not to leap from lab demonstrations to generally intelligent robots. Instead, our plan is to climb the gradient of real-world variability and capture more of the spectrum.”

“We expect our robots to do everything one day, too. We just believe that:

“Everything” is made up of a continuous spectrum of small “somethings.”

Each of those “somethings,” whether it’s packing a bent cardboard box or checking a cow’s temperature through its anus (a real use case), requires use-case-specific data to be done well.

By deploying our robots in the field today, we get paid to collect the data we need to improve our models. That includes the most valuable data of all: intervention data when a robot fails.

When we find a new edge case, we can iterate on our entire system of variable robots. This is because we are fully vertically integrated, including data collection, the models, the firmware, and the physical arm.

Our plan is to get paid to eat the spectrum.

In the process, we plan to collect data no one else can. We’ll then use this data, which is tailor made for our robots, to iterate on the whole system quickly enough to get to general economic usefulness before the giant leap, straight-shot approaches do.

There’s a lot of context behind our bet. The first and most important thing you need to understand is that robotics is bottlenecked on data.”

“…LLMs had it relatively easy. The entire internet existed as a pre-built training corpus. There is so much more information on the internet than you could ever imagine. Any question you might ask an LLM, the internet has probably asked and answered. The hard part was building architectures that could learn from it all.

Robotics has the opposite problem.”

“The architectures largely exist. We’ve seen real breakthroughs in robot learning over the last few years as key ideas from large language models get applied to physical systems. For example, Toyota Research Institute’sDiffusion Policy shows that treating robot control policies as generative models can dramatically improve how quickly robots learn dexterous manipulation skills.”

“…those papers also all found something similar. For those remarkable innovations to happen with any reasonable success rate, you need data on your specific robot, doing your specific task, in your specific environment.

If you train a robot to fold shirts and then ask it to fold a shirt, it works. Put the shirts in different environments, on different tables, in different lighting. It still works. The model has learned to generalize within the distribution of “shirt folding.”

But then try asking it to hang a jacket or stack towels or to do anything meaningfully different from shirt folding. It fails. It’s not dumb. It’s just never seen someone do those things.”

“Robots can interpolate within their training distribution. They struggle outside of it.

This is true for LLMs, too. It’s just that their training data sets are so large that there isn’t much out of distribution anymore.

This is unlikely to be solved with more compute or better algorithms. It’s a fundamental characteristic of how these models work. They need examples of the thing you want them to do.

So how do you collect example data?

One answer would be to create it in the lab. Come up with all of the edge cases you can think of and throw them at your robots. As John Carmack warned, however, “reality has a surprising amount of detail.” The real world chuckles at your researchers’ edge cases and sends even edgier ones.

Another answer would be to just film videos of people doing all of the things that you’d want the robots to do. Research has shown signs of life here.”

“Ultimately, general video may lift the starting capabilities of a model. But it still doesn’t remove the need for the on-robot data for the final policy, even for simple household pick-and-place tasks (and industrial tasks will need much more data). For one thing, robots need data in 3D, including torques and forces, and the data needs to occur through time. They almost need to feel the movements. Videos don’t have this data and text certainly doesn’t.”

“A lot of the modern robotics-AI wave started the same way: pretrain perception, learn actions from scratch. Meaning, teach the robot how to perceive and let it learn by perceiving.

Take Toyota Research Institute’s Diffusion Policy. The vision encoder (the part that turns pixels into something the model can use) is pretrained on internet-scale images, but the action model begins basically empty.”

“As people watched more videos, their confidence climbed sharply. Meanwhile, their actual performance barely moved, or even got worse.

That’s the embodiment gap. Video tells you what to do, but not what it feels like to do it. You can watch someone moonwalk all day. You still won’t feel how the floor grips your shoe, how much pressure transfers to your toes, how to modulate tension without faceplanting.

And robots have it worse than humans. At least we have priors. Robots have sensors and math.

I’m going to get a little spicy here.

If you’re not paying very close attention, it looks like feeding robots internet videos is working.

Watch Skild’s “learning by watching” demos closely. Only the simplest tasks use “one hour of human data.” More impressive demos are nestled in the middle of the video without that label. And the videos aren’t random ones pulled from YouTube either. They’re carefully collected first-person recordings from head-mounted cameras. Is doing all of this that much easier than just using the robots?

In short, there are three big reasons video isn’t enough:

Coverage: internet video doesn’t cover the weird, constrained, adversarial reality of industrial environments.

Data efficiency: learning from video alone typically takes orders of magnitude more data than learning from robot-collected data, because the mapping from pixels to action is underconstrained without embodied sensing.

Missing forces: two surfaces can look identical and behave completely differently. Video can’t disambiguate friction. The robot finds out the fun way.”

Then, you still have the translation problem: human hands aren’t robot grippers, kinematics differ, scale differs, compliance differs, systematic error shows up unless you train with the exact end effector you’ll deploy.

Which is why many of these companies end up quietly going back to teleoperation.

Human video is useful for pretraining. But weakly grounded data has a real cost: you can either do the hard work of actually climbing the hill, or you can wander sideways for a long time and call it progress.”

“When you do real things in the real world, physics gets messy. Real tasks involve soft materials, deformed packaging, fluids, cable routing, wear-dependent friction, tight tolerances, and contact-dominated outcomes.

You can simulate parts of this, but doing it broadly and accurately becomes a massive hand-crafted effort. And you still won’t match the edge cases you see in production. Again, you might as well do the real thing.”

“Waymo is a great example. Waymo uses a ton of simulation today, but real-world data collection from humans driving cars came long before the world model. Do you remember how long human Google workers drove those silly looking cars around collecting data before Waymo ever took its first autonomous ride? As the company wrote in a recent blog post, “There is simply no substitute for this volume of real-world fully autonomous experience — no amount of simulation, manually driven data collection, or operations with a test driver can replicate the spectrum of situations and reactions the Waymo Driver encounters when it’s fully in charge.”

You need to collect that data in the real world, and then you can replay and amplify it in sim. That’s how you get the last few “nines.”

“So simulation is valuable, but it’s still not a replacement for real data collection.

The highest-leverage use of sim is after deployment: when real robots surface real failure modes, and sim is used to reproduce and multiply those rare cases.

Which brings us back to first principles.

So What’s the Best Way to Train a Robot? (Like You’d Train a Human)

Think about how you train a human.

For simple tasks, text works. For slightly harder ones, a checklist helps. But most real factory work isn’t that simple. You need alignment, timing, judgment, recovery, and the ability to handle “that thing that happens sometimes.”

At that point, demonstration wins. It’s the most information-dense way to transfer intent. This is why people in the trades become apprentices.

It’s the same for robots. And it’s okay if a robot takes minutes or even hours to learn a task, as long as the learning signal is high quality.”

“The Giant Leap, the point at which the model has suddenly seen enough and can do anything, isn’t real. It is enticing and sexy (maybe in part it’s enticing and sexy because it’s always just out of reach). But it doesn’t exist.

Even the smartest humans need training and direction. Terence Tao would need years to become an expert welder.

We think the answer is simply committing to taking the time to collect the right data. Robot-specific, task-specific, high-fidelity data, even if it means fewer flashy internet demos.

Three things follow from this:

You will always need robot-specific data.

The highest-quality way to convey a task is to show it (teleop or direct manipulation).

Once you have strong domain-specific data, low-quality vision data from unrelated tasks doesn’t help much.

LLMs feel magical because they interpolate across the full distribution of human text. Robots don’t have that luxury.

To be clear, my contention is not that video, simulation, and better models aren’t useful. They clearly are. My contention is that with them, you still need to collect the right data.”

“…intervention data at the moment of failure is the best data. We’ve learned that collecting data right around where the thing failed allows us to efficiently pick up all of the edge cases, and this is often the minimum training data we need. We concentrate at the boundary where autonomy breaks instead of just collecting data on the 95% of stuff we do flawlessly over and over again, and we learn where reality actually disagrees with our model. And because our robots are the ones generating the failures — not humans — we learn where our robots fail.

Learning where robots fail is important.

There’s a mismatch when you train a robot on human demonstrations: the human operates in their own state distribution, but the robot will drift into states the human never showed it. Better to let the robot fail and act quickly to resolve.”

“The promise of humanoids is captivating to many investors (especially Parkway Venture Capital). Understandably so. “The world was created for the human API.” It sounds so nice, and it’s true to some extent.

But that dream collides uncomfortably with reality. As I was recently quoted saying in the WSJ Tesla Optimus Story: “With a humanoid, if you cut the power, it’s inherently unstable so it can fall on someone.” And “for a factory, a warehouse or agriculture, legs are often inferior to wheels.”

I’m incentivized to say that, so don’t take it from me. In the same story, the author writes that, “inside the company [Tesla], some manufacturing engineers said they questioned whether Optimus would actually be useful in factories. While the bot proved capable at monotonous tasks like sorting objects, the former engineers said they thought most factory jobs are better off being done by robots with shapes designed for the specific task.” (That’s what we do with our modular design, by the way. Thanks, Tesla engineers.)”

“The Bitter Lesson in Robotics is that leveraging real-world data is ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.

You can’t Bitter Lesson your way to victory if you don’t have the training data, and you can’t get the training data without deployment. What Sutton would really suggest, I think, is to get as many robots in the field as possible and then let them learn in a way that is interactive, continual, and self-improving.”

“We believe, like so many of the people working in our industry do, that there will be no bigger improvement to human flourishing than successfully putting robots to work in the real economy. We are on the precipice of labor on-tap, powered by electrons and intelligence. That means cheaper, better goods. It means freeing humans from the work they don’t enjoy. Being a farmer is more fun when you don’t have to take the cow’s temperature yourself. It means that the gap between thought and thing practically disappears. And those are just the first-order effects. We can’t know ahead of time what fascinating things people will dream up for our abundant robotics labor force to do; all we can know is that they will be things people find useful.

We all believe this. We all want to produce a giant leap for mankind. The open question is how we get from here to there.”

5 Big thinking

Courtney Smith explores what comes after mastery…it’s a journey worth taking - do it here in full…

Some Takeaways

“There is a moment that arrives quietly, often unnoticed by anyone else.

It comes after competence has been proven, after access has been earned, after the systems you built have begun to work.

From the outside, nothing is wrong.

From the inside, something no longer feels entirely true.

This is not burnout.

It is not boredom.

And it is not a lack of ambition.

It is the subtle dissonance that appears when mastery has been achieved, but the structures carrying your life - your work, your influence, your commitments - have not yet caught up to who you are becoming.”

“After mastery, the question is no longer how to improve the system.

It is whether the system itself still reflects what is true.

When this dissonance appears, most accomplished leaders assume it is personal.

They look for the source in motivation, mindset, or discipline. They question their focus. They add new goals, new strategies, or new structures, assuming something inside needs to be corrected.

That reflex makes sense. It has worked before.

But more often than not, the friction is not internal. It is structural.

Identity has evolved faster than the systems designed to express it. Influence has expanded, but the containers holding it have remained static. Capital (time, attention, relationships, resources) is still organized around an earlier version of the work.

Nothing is broken.

The architecture is simply outdated.”

“At this stage, optimization becomes a blunt instrument. It increases efficiency inside structures that no longer reflect what is true, amplifying tension rather than resolving it.

What is required instead is discernment: an external vantage point capable of seeing where the system no longer matches the person it is meant to serve.

This shift is rarely dramatic. It is a reordering.

The instincts that once drove progress begin to invert.

What mattered most during the climb (speed, leverage, accumulation) becomes less useful here. In its place, a different set of constraints emerges. Fewer decisions, but heavier ones. Fewer commitments, but more consequential.

Attention becomes the scarce resource.

Timing matters more than momentum.

Coherence begins to outweigh scale.

The question quietly changes.

Not what else can I build. But what deserves to be carried forward… and what no longer does.”

“After mastery, progress is no longer additive.

It is subtractive - and therefore unfamiliar.

This stage offers little external validation.

The world continues to reward the patterns that produced success, even when they no longer align internally. Letting go of those patterns can look irrational from the outside. Continuing them often feels increasingly costly from the inside.

That tension is not a failure. It is a signal.

What follows mastery is not reinvention. It is honesty.

Not what should I build next.

Not how do I scale this further.

But what wants to emerge now, and what structures need to change to support it.

That question cannot be rushed. It cannot be answered through force or acceleration. It asks instead for restraint, for discernment, and for the willingness to let alignment lead.

After mastery, the work is no longer about proving capacity. It is about stewarding coherence.

And that is a different kind of discipline entirely.”

6 Choice Management

Have a Great weekend when You get to that stage,

Sune