Weekend Food for Thought WFFT

Today's Special: Power of Context, Innovation, Vertical integration, and extra delicacies!

Hello from New York,

I hope you had an interesting and productive week.

Carl Schurz stated that; "Ideas are like stars; you will not succeed in touching them with your hands. But like seafarers, you choose them as your guides, and following them, you will reach your destination.”

Below flows some ideas that my help guide your curiosity in interesting new directions…

1 Getting Visual

2 If You Read One Thing Today - Make Sure it is This

3 Consequential Thinking about Consequential Matters

4 Big Ideas

5 Big thinking

6 Swim

If you like some background music with your reading - check this out:

1 Getting Visual

The Long-View: The Power of Innovation: “Moore’s Law, coined by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in the 1965 when he was asked to predict what would happen in silicon components over 10 years. He predicted that transistor counts would double roughly every two years, driving exponential leaps in computing power. Yet each anticipated limit, whether from physics or economics, has sparked new waves of innovation such as GPUs, 3D chip stacking and quantum architectures. Moore’s Law was never a single forever-exponential; it is better viewed as a relay race of logistic technology waves. The baton is still being passed – just more slowly, and with ever-higher stakes – so the graph still looks exponential even though the underlying sprint has become a succession of S-curves. For decades, making computer chips smaller let engineers simply turn up the speed without using extra power – a trend called Dennard Scaling, which worked hand-in-hand with Moore’s Law. But physics pushed back. Smaller parts started to overheat and by the early 2000s manufacturers hit a ceiling: raising the clock speed any higher would melt the chip. The solution was to add more “brains” (cores) that share the work instead of asking one core to sprint faster and hotter. That shift to multi-core processors, explored in detail here, let performance keep climbing without turning your laptop into a space heater. Still, innovations continued, reaffirming the adaptability of these foundational laws.” - Azeem Azhar

Innovating against the constraints… Successive NVIDIA GPU generations have cut energy per LLM token 105,000x in 10 years, collapsing inference cost. The pursuit of doing more with less continuous…

Long Human Ingenuity - Top AI Supercomputer power has doubled every 9 months…

Power Dynamics - "Swanson’s Law is the solar-power version of a volume discount because each time the world’s total solar capacity doubles, the price of a panel drops by roughly 20%. Over a few short decades those repeated cuts have worked like compound interest in reverse – turning solar from an expensive science-fair project into, in many places, the cheapest way on Earth to make electricity. It’s a textbook example of how steady, exponential cost declines can flip a market on its head.” Azeem Azhar

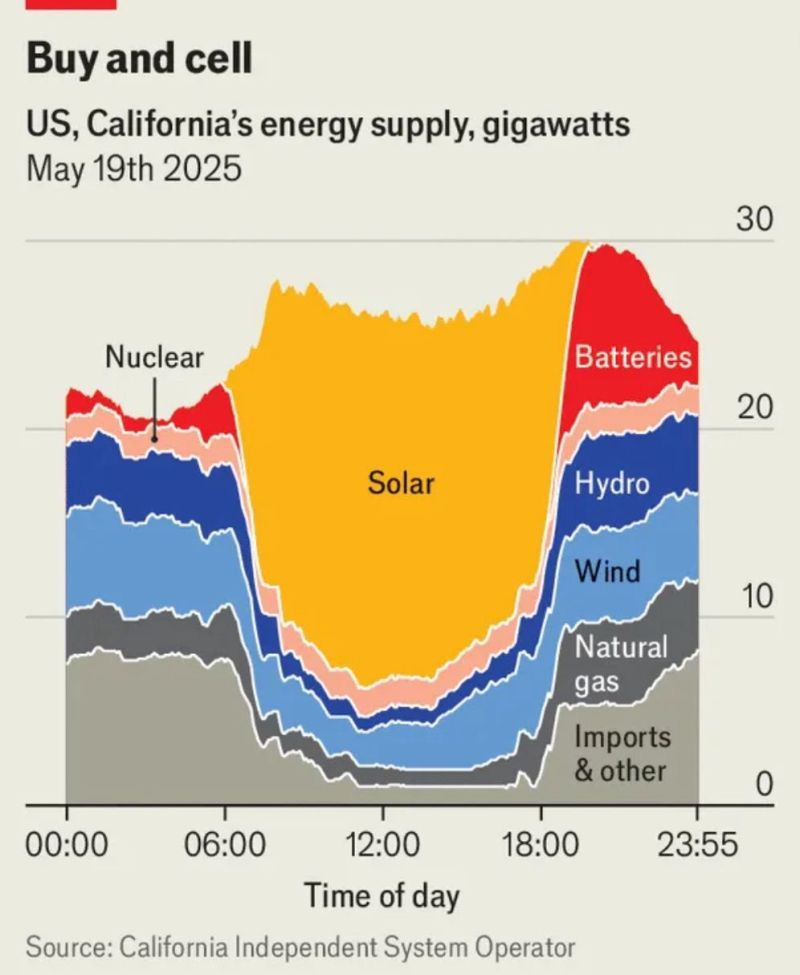

A Day in California through the lens of CISO…

Electricity is fundamental to the functioning of modern economies. China generated over 10,000 TWh of electricity in 2024. For context, that’s more than the combined output of the U.S., EU, and India—the next three biggest producers. China’s rapid rise in electricity generation fueled its equally rapid economic growth. In fact, research found that 1% increase in its electricity production corresponded to 0.17% increase in GDP (but not vice-versa). China also produces the most wind and solar energy in the world.

Learn more here: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ranked-top-countries-by-annual-electricity-production-1985-2024/

Downer in Startup Land - Down rounds remain stubbornly high for US Startups…(Unless you are building in AI)…

The supposed Demise of the Bay was short-lived - Silicon Valley is home to the leading AI companies and they lead the fund raising…

2 If You Read One Thing Today - Make Sure it is This

What role will AI have in our lives as it continues to improve and scale? Tina He and friends go exploring and discovers the power of context…Go explore it all for yourself here:

Get the full paper here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5277474

Some Takeaways

“Rewind to an idea that once lit up machine learning: "Attention is all you need," the breakthrough that showed AI models could focus on relevant parts of data without complex memory systems.

Yet, the next decade may prove that attention is only as powerful as the context you feed it.

The race for AI dominance has shifted from who has the best models to who controls and understands user context.”

The Promise of (and the Race for) Context

A few definitions to get on the same page:

Context: All signals available to a product, including environmental cues, device state, user history, and intent.

Context Window: The quantity and recency of information processed by a model.

Memory: Persistent context carried forward across sessions.

Personal Context Infrastructure: Systems that aggregate, store, update, and share context between services.

Context Boundary: Rules defining what information is accessible and how memory is managed.

Effective context-aware systems operate across four layers:

Immediate: Current conversation or task.

Session: Today's work or project.

Personal: Preferences, patterns, relationships.

Environmental: Location, schedule, available devices.

For as long as we’ve dreamed of AI, we’ve longed for machines that not only “get” our explicit asks but seem to understand us, the way a longtime friend finishes your sentence or a creative partner anticipates your next thought.

We want AI to evolve from a mere notetaker to a genuine collaborator, a presence that knows when to nudge, when to listen, and when to step back.

The most valuable resource isn’t algorithms, compute, or even just data.

It’s context: the mosaic of real-time signals, history, recent mood shifts, stray calendar invites, and the live-wire pattern that is “you, right now.

There’s a collective land grab for context.

Who gets to see it? Who stores it? Who profits from it? Whoever answers these questions wins the right to shape what AI is for the next generation.”

From Data Hoarding to Context Awareness

Historically, platforms vacuumed clicks and scrolls into massive datasets.

Today, with smarter models and expressive interfaces, AI builds "digital twins," live models of user intent and state. Recent context now vastly outweighs stale historical data.

For example, a health-tracking wearable that alerts you based on your current heart rate, hydration, or stress levels rather than past averages. Smart home devices that adjust lighting, temperature, or music based on immediate activities or conversations, not historical usage patterns. Productivity apps like Linear or Notion highlighting tasks that are actively being discussed in real-time collaboration.”

Context Is Generated, And Earned

Context isn’t something you can just scrape or surveil. You have to earn it.

The interfaces we choose—whether chat, camera, calendar, or code editor—are invitations. They shape not only how much context we’ll willingly share, but also the kind that gets generated. A design tool will surface creative patterning. A health wearable will log your physical rhythms. An intimate AI chat will prompt you to disclose the messy, heartfelt stuff you’d never type into a search box.

The big unlock will come from combining data from different domains.

Your Spotify listens, Dexcom data, and Notion scratchpads are all different “eyes and ears” on your life. The winner might just be whoever stitches the most relevant slices together in a way you actually trust.”

Success comes from mastering three technical layers working together.

Collection Layer: APIs, sensors, and behavioral signals. GitHub Copilot doesn't just read your code—it notices your coding patterns, preferred libraries, and when you're most likely to introduce bugs.

Processing Layer: Where raw signals become intelligence. This handles context synthesis (connecting dots across data sources), privacy filtering (what gets remembered vs. discarded), and relevance ranking (what matters right now).

Application Layer: Context becomes action. The AI that finishes your sentences, the assistant that avoids scheduling calls during your kid's soccer practice, the design tool that suggests your recent color themes.

The winners either build all three layers (OpenAI's full-stack approach) or dominate one layer while integrating seamlessly with others (Calendly owns scheduling context, Linear owns dev project context).

This architecture explains why context portability is hard. You're not just moving data files, you're losing the processing logic that learned your patterns.

Trust becomes a competitive advantage: users share more context with systems they trust, creating a flywheel effect across all three layers.”

“The dream: a portable context engine that travels with you, layerable across services, encrypted and privacy-respecting by default. In theory, you could “train” a new chatbot on your real personality—or let a digital agent represent you—without starting from scratch every time you switch apps.

In practice, privacy and security challenges remain complex. But the direction is clear: a future where your context truly belongs to you, freely movable with permissions tailored to your preferences.”

Why Context Stays Locked Up

Legacy platforms have no reason to help you escape. The business model is simple: lock in as much context as possible, then charge rent (in money, attention, or both) for access to your own life. Regulation (GDPR, DMA) is starting to force cracks in these walls. The friction is part of the moat.”

“Context exhibits powerful network effects that work against portability. Each additional piece of context about a user doesn't just add linear value,it creates exponential improvements in personalization. A company with 80% of your context can provide dramatically better service than one with 20%, making it economically irrational for users to fragment their context across providers. This creates a natural monopolization force where winner-takes-most dynamics emerge.”

“The computational costs also become staggering. Maintaining a rich, multi-layered context for millions of users requires massive infrastructure. Every additional context signal exponentially increases processing complexity. This creates a natural centralization force, only tech giants can afford to maintain context at scale, reinforcing the very lock-in we're trying to escape.

Most critically, we face the privacy paradox: users simultaneously crave deep personalization ("know me like a best friend") while fearing surveillance ("but don't watch me"). This isn't irrational, it reflects the genuine risk that context powerful enough to anticipate your needs is also powerful enough to manipulate them. The same context that helps an AI therapist provide better support could be weaponized for targeted exploitation. No technical architecture fully resolves this tension.”

End State: Agency or Enclosure?

We're at an inflection point. The AI race is shifting from model performance to context mastery. The winners won't be those with the biggest models, but those who build the most trusted context infrastructure.

If you're a builder: Start with one killer use case that makes context portability irresistible. Focus on immediate value, not abstract promises. Remember: Spotify didn't pitch "context awareness"—they just made music feel personal.

If you're a platform: Choose your strategy now. Will you lock in context and milk it or become the trusted context layer others build on (the Stripe playbook)?

If you're a user: Your context is your leverage. Support products that give you control, not those that mine you for data.

The technical challenges are real. Interoperability is hard, computation is expensive, and privacy is paradoxical. But these are engineering problems, not laws of physics. The first products to crack the code will trigger an avalanche. Once users experience a truly portable, powerful context, there's no going back to silos.

Context is all you need, but only if you build for user agency, not addiction; for portability, not lock-in; for trust, not surveillance.”

3 Consequential Thinking about Consequential Matters

JS Tan’s ‘Value Added’ Substack is a good value add to your reading - go check it out…Here he takes a look at the shift back to vertical integration and how the way firms are structured can influence whether innovation comes from the top or from the factory floor. The concepts of product and process level innovation are key aspects to understand if you are seeking to understand innovation and business moats as well as the larger geopolitical trends playing out currently under the somewhat flawed “trade wars” banner. It’s consequential thinking about consequential matters - go do your own research - start with Tan’s perspectives here:

Part 1 can be accessed here:

Part 2 can be accessed here:

Some Takeaways

“…how frontier corporate strategies evolved from building it all to building nothing at all. The Fordist firms of the postwar era were vertically integrated giants, with production capabilities spanning every stage of the value chain.

But beginning in the 1970s, the rise of shareholder value primacy, outsourcing, and the IT revolution transformed how leading firms operated. Labor- and capital-intensive production was offshored, while knowledge-intensive functions—like R&D, design, and IP management—were kept in-house.

Apple is a good illustration of the new model. It designs its products in California, retains tight control over its software ecosystem and intellectual property, but outsources nearly all of its manufacturing to contractors like Foxconn in China. From tech firms like Apple to consumer brands like Nike, firms in this era focused less on making things and more on extracting value through intangible assets: patents, licenses, platform fees, brand markups, and financial instruments.

This model of vertical fragmentation made many American firms fabulously profitable by allowing them to tap into cheap labor and deregulated markets abroad. But those profits came at a cost.

This fragmentation gutted the American working class, who were once the anchor of Fordist production and shared in the rewards of rising productivity. And, as many have pointed out, decades of offshoring has eroded the nation’s capacity to produce at home.

Today, frontier firms are once again shifting their organizational strategies. From cloud giants to EV manufacturers, some of the most influential companies of the 21st century are turning back to vertical integration.

However, this shift is not a response to the social costs of vertical fragmentation. Instead, it reflects a strategic pivot in the type of innovation these firms now prioritize.”

From the horizontal platform to the vertical cloud

During the Web 2.0 platform era, tech firms were universally seen as asset-light, agile, and defined by their software—not their hardware. It wasn’t that people ignored the underlying infrastructure these platforms depended on, but rather that building and maintaining that infrastructure was viewed as a low-margin, low-status task best left to less innovative players. Instead, the platform business model demanded scale, rather than control over every layer of the technology stack.

The most competitive firms were asset-light, owning as little of the production stack as possible while focusing only on maximizing horizontal expansion.

This imperative for rapid expansion meant platform firms needed to decouple their software from underlying hardware, ensuring users could access their services across any operating system or device—whether Windows, Linux, or Mac; Android or iOS. It also shaped their approach to mergers and acquisitions, leading them to prioritize the purchase of horizontal competitors rather than complementary firms upstream. Facebook’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp, for example, were aimed at consolidating user bases and expanding reach rather than integrating new technological capabilities.

Over the past decade, some of the biggest players in tech have repositioned themselves around cloud computing and AI as the next major frontier of innovation. In the process, they’ve begun to reverse a decades-long trend toward horizontal sprawl by vertically integrating elements of the stack.

The leading cloud firms—Amazon, Microsoft, and Google—are now investing more heavily than ever in building physical infrastructure as a core source of competitive advantage. Their competencies extend well beyond the software layer (e.g., virtualization, data and AI services, and developer tools) and today includes building physical infrastructure such as custom chips, specialized server racks and cooling systems, and massive data centers. Even the energy required to power these facilities are no longer left to the market.

Companies like Microsoft are investing directly in renewable energy projects to secure a stable, long-term power supply for their increasingly energy-intensive operations.

Initially, cloud infrastructure followed the logic of the platform era: fill data centers with off-the-shelf, commodity hardware and prioritize universal compatibility. The goal was to maximize flexibility such that any software could run on any hardware. But as workloads have grown more complex—especially with the rise of AI—the cloud's flexibility-first paradigm has started to show its limits. Performance bottlenecks, latency issues, or sheer limitations in hardware performance have pushed cloud firms to pay closer attention to the underlying hardware.

In response, the most competitive cloud providers are moving away from hardware-agnosticism and embracing full-stack control. Indeed, a key part of their competitive advantage now lies in the recoupling of software and hardware—developing specialized infrastructure tailored for specific workloads. Google’s machine learning library, TensorFlow, for example, is tightly integrated with its custom-made Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) to maximize performance and efficiency.”

Automaker's shift from "just-in-time" production to end-to-end control

The auto industry has undergone a parallel transformation. In the 1980s, U.S. automakers suddenly found themselves outcompeted by their Japanese rivals. Japanese car makers weren’t offering radically different vehicles, but they gained a decisive edge on price—an advantage made possible by organizational innovations at the firm level. Instead of following the Fordist model that had dominated U.S. (and to some extent European) auto manufacturing in the mid-20th century, Japanese automakers pioneered a lean, just-in-time production system that emphasized flexibility and cost-cutting by minimizing inventory and relying on tightly managed supply chains.

Toyota became the most successful practitioner of this model, ultimately surpassing its American rivals to become the world’s largest automaker by the 2000s. And its influence extended well beyond the auto industry, shaping the strategies of firms like Apple, which adopted similar principles of outsourcing and tight control over a global supplier network.

Today, however, the pendulum is swinging back. In contrast to the vertically fragmented, just-in-time model pioneered by Toyota, the new frontrunners of the EV race—Tesla and BYD—are embracing end-to-end control. Tesla’s vertical integration spans multiple layers of its business—from in-house manufacturing in its highly automated Gigafactories to software development for vehicle systems and driver's assistance. The company has also invested in producing its own battery cells with strategic partners (such as Panasonic) which allows the company to bring in outside expertise while keeping control internal. Even in distribution, Tesla bypasses traditional dealerships, selling directly to consumers and maintaining full control over the customer relationship.

BYD, China's giant EV maker who surpassed Tesla in 2023 in EV units sold, is even more vertically integrated. Where Tesla's Gigafactories are highly automated, BYD utilizes China's supply of cheap labor to manufacture its cars. But its major competitive advantage is in its batteries, arguably the most critical component of an electric vehicle, which are made entirely in-house. Unlike Tesla, that still sources the majority of its batteries from external producers like CATL (despite producing their own batteries), BYD began as a battery company, supplying rechargeable batteries for mobile phones before expanding into the automotive sector.

Today, BYD not only produces its own EVs and batteries at scale, but it is vertically integrated across the value chain: from manufacturing their own semiconductors to building in-house software and electric motors. BYD's ambition for vertical integration even extends upstream into lithium mining and downstream into owning its own massive carrier ships for shipping its cars aboard. The company also has facilities to recycle end-of-life batteries.”

Part 1 Conclusion

From cloud computing to EV manufacturing, some of the most innovative firms in the global economy are embracing this neo-Fordist approach and bringing increasing portions of their supply chains under direct control. But this pattern isn’t limited to just clouds and cars.

In retail, companies like Home Depot and IKEA are expanding into logistics by chartering their own container ships, with IKEA even going a step further by purchasing its own shipping containers. IKEA is also extending its control upstream, having acquired a Romanian forest in 2015 and forestland in Alabama in 2018. These purchases are aimed at securing raw materials and building a more sustainable and resilient supply chain.

Even in media, Netflix has moved beyond content distribution into full-scale production, building its own studios and producing original programming. Conversely, legacy entertainment companies are moving in the opposite direction—expanding aggressively into distribution by launching their own streaming platforms, as seen with Disney+. Across sectors, vertical integration is re-emerging not as a relic of the past, but as a forward-looking strategy for resilience, coordination, and control.

However, this doesn’t mean all firms will follow suit in this direction. Vertical integration is capital-intensive and comes with high coordination costs. This type of organizational maneuver is also usually (but not always) done from a position of market dominance.

In a global economy still shaped by robust supply chains—trade tensions notwithstanding—sourcing upstream components from around the world remains the more viable option for many firms, especially in low-margin sectors. For most firms, the benefits of tighter supply chain control simply don’t outweigh the costs.”

Part 2 - Take Aways

“Aside from creating more resilient supply chains in the face of global disruptions and rising geopolitical tensions, vertical integration may be increasingly important in sectors where process innovation (rather than product innovation) is critical.

Product innovation in vertically fragmented firms

First, let us begin by looking at the complementarity between vertically fragmented firms and product innovation. That is, innovation that focuses on developing new features, services, or user experiences. In this model, technological innovation is decoupled from production. The apex firm dictates design and product changes, often resulting in entirely new supply chains. This structure rewards flexible value chains where disposable, market-mediated relationships with suppliers is an advantage.”

“The apex firm maintains control over the product design and sets the specifications that manufacturers must follow. As a result, improvements in the production process do not improve the final product outside of reducing its price.

In firms optimized for product innovation, the primary benchmark for success is consumer uptake. Innovation is seen as originating from formal R&D units rather than the factory floor.”

Process innovation in vertically integrated firms

Vertically integrated firms, by contrast, are better positioned to reap the benefits of process innovation, which is all about improving how things are produced. This includes new production techniques or engineering improvements on the factory floor. Process innovations are discovered through hands-on experience with the materials, tools, and workflows involved with production—what the economist Kenneth Arrow called learning by doing.”

“In sectors where advances in production establishes a firm’s competitive advantage (such as semiconductors, solar panels, or batteries) there tends are clear technical benchmarks for success (smaller chip sizes, higher energy efficiency, or greater storage capacity). This is crucial because it makes process innovation measurable. This means that manufacturers are not only expected to improve yield and reduce costs, but also to innovate in their production processes in order to push the boundaries of these technical benchmarks.

It’s important to recognize not just how innovation happens, but where it takes place. In sectors driven by product innovation, breakthroughs often come from R&D labs, typically within the apex firm. But in production-oriented industries, innovation frequently emerges from within the value chain itself. This matters because changes in one stage of production can ripple through the entire value chain. For instance, a new material used in a single component might compel downstream changes such as in the products final design. It might also require different upstream inputs.

In this model, innovation can emerge at any point along the value chain. And rather than allowing these production-based insights to remain siloed at the supplier level, vertically integrated firms are able to capture and leverage them. On top of that, owning the value chain means they can better coordinate across it, putting them in a stronger position to translate localized improvements into system-wide gains.”

“Vertical integration is not merely a return to past organizational practices. It represents a renewed effort by frontier firms to gain a competitive edge through process innovation. Whether this trend remains confined to leading companies or evolves into a broader restructuring of capitalism is an open question. Either way, the resurgence of vertical integration should be a reminder that innovation comes not only in R&D labs but also from production on the factory floor.”

4 Big Ideas

Meeker, Simons, Chae & Krey dropped a 340 page visual festival of insights on the tech trend of this decade (and likely beyond): Artificial Intelligence (AI). Load up on espresso and go explore it in full here:

https://www.bondcap.com/reports/tai

Some Takeaways

“We set out to compile foundational trends related to AI. A starting collection of several disparate datapoints turned into this beast.

As soon as we updated one chart, we often had to update another – a data game of whack-a-mole…a pattern that shows no sign of stopping…and will grow more complex as competition among tech incumbents, emerging attackers and sovereigns accelerates.

Vint Cerf, one of the ‘Founders of the Internet,’ said in 1999, ‘…they say a year in the Internet business is like a dog year – equivalent to seven years in a regular person's life.’ At the time, the pace of change catalyzed by the internet was unprecedented.

Consider now that AI user and usage trending is ramping materially faster…and the machines can outpace us.

The pace and scope of change related to the artificial intelligence technology evolution is indeed unprecedented, as supported by the data. This document is filled with user, usage and revenue charts that go up-and-to-the-right…often supported by spending charts that also go up-and-to-the right.

Creators / bettors / consumers are taking advantage of global internet rails that are accessible to 5.5B citizens via connected devices; ever-growing digital datasets that have been in the making for over three decades; breakthrough large language models (LLMs) that – in effect – found freedom with the November 2022 launch of

OpenAI’s ChatGPT with its extremely easy-to-use / speedy user interface.

In addition, relatively new AI company founders have been especially aggressive about innovation / product releases / investments / acquisitions / cash burn and capital raises. At the same time, more traditional tech companies (often with founder involvement) have increasingly directed more of their hefty free cash flows toward AI in efforts to drive growth and fend off attackers.

And global competition – especially related to China and USA tech developments – is acute.”

To say the world is changing at unprecedented rates is an understatement.

Rapid and transformative technology innovation / adoption represent key underpinnings of these changes. As does leadership evolution for the global powers.

Google’s founding mission (1998) was to ‘organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.’ Alibaba’s founding mission (1999) was to ‘make it easy to do business anywhere.’ Facebook’s founding mission (2004) was ‘to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.’

Fast forward to today with the world’s organized, connected and accessible information being supercharged by artificial intelligence, accelerating computing power, and semi-borderless capital…all driving massive change.

Sport provides a good analogy for AI’s constant improvements. As athletes continue to wow us and break records, their talent is increasingly enhanced by better data / inputs / training. The same is true for businesses, where computers are ingesting massive datasets to get smarter and more competitive.

Breakthroughs in large models, cost-per-token declines, open-source proliferation and chip performance improvements are making new tech advances increasingly more powerful, accessible, and economically viable.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT – based on user / usage / monetization metrics – is history’s biggest ‘overnight’ success (nine years post-founding). AI usage is surging among consumers, developers, enterprises and governments.

And unlike the Internet 1.0 revolution – where technology started in the USA and steadily diffused globally – ChatGPT hit the world stage all at once, growing in most global regions simultaneously.

Meanwhile, platform incumbents and emerging challengers are racing to build and deploy the next layers of AI infrastructure: agentic interfaces, enterprise copilots, real-world autonomous systems, and sovereign models.

Rapid advances in artificial intelligence, compute infrastructure, and global connectivity are fundamentally reshaping how work gets done, how capital is deployed, and how leadership is defined – across both companies and countries.

At the same time, we have leadership evolution among the global powers, each of whom is challenging the other’s competitive and comparative advantage. We see the world’s most powerful countries revved up by varying degrees of economic / societal / territorial aspiration…”

“…Increasingly, two hefty forces – technological and geopolitical – are intertwining. Andrew Bosworth (Meta Platforms CTO), on a recent ‘Possible’ podcast described the current state of AI as our space race and the people we’re discussing, especially China, are highly capable…there’s very few secrets. And there’s just progress. And you want to make sure that you’re never behind.

The reality is AI leadership could beget geopolitical leadership – and not vice-versa. This state of affairs brings tremendous uncertainty…yet it leads us back to one of our favorite quotes – Statistically speaking, the world doesn’t end that often, from former T. Rowe Price Chairman and CEO Brian Rogers.

As investors, we always assume everything can go wrong, but the exciting part is the consideration of what can go right.

Time and time again, the case for optimism is one of the best bets one can make.

The magic of watching AI do your work for you feels like the early days of email and web search – technologies that fundamentally changed our world. The better / faster / cheaper impacts of AI seem just as magical, but even quicker.

No doubt, these are also dangerous and uncertain times.

But a long-term case for optimism for artificial intelligence is based on the idea that intense competition and innovation…increasingly-accessible compute…rapidly-rising global adoption of AI-infused technology…and thoughtful and calculated leadership can foster sufficient trepidation and respect, that in turn, could lead to Mutually Assured Deterrence.

For some, the evolution of AI will create a race to the bottom; for others, it will create a race to the top.

The speculative and frenetic forces of capitalism and creative destruction are tectonic.

It’s undeniable that it’s ‘game on,’ especially with the USA and China and the tech powerhouses charging ahead.”

5 Big thinking

Kevin Kelly shared these perspectives on the need for more than pure intelligence to solve problems and create solutions back in 2021 - plenty of food for thought in this short pondering…

https://kk.org/thetechnium/the-thinkism-fallacy/

Some Takeaways

“Thinkism is the fallacy that problems can be solved by greater intelligence alone. Thinkism is a fallacy that is often promoted by smart guys who like to think. In their own heads, they think their own success is due to their intelligence, and that therefore more intelligence brings greater success in all things. But in reality IQ is overrated especially as a means to solve problems. This view ignores the many other factors that solve problems. Such as data, experience, and creativity.”

“Between not knowing how things work and actually knowing how they work, stands tons of experiments in the real world which yields tons and tons of data that will be required to form the correct working hypothesis. Thinking about the potential data will not yield the correct data. Thinking is only part of science; maybe even a small part.”

“IQ is overrated in science. The most innovative theories and experiments are not necessarily coming from the smartest people.

Often the most imaginative succeed when the smartest don’t.

Sometime those that are most persistent win; they keep doing the experiment until it works.

On the other hand we all know really smart people who do dumb things. Intelligence is needed but is not sufficient.

Artificial intelligence is on its way to become a commodity. You’ll be able to buy as much IQ as you want, or can afford. We’ll soon apply large doses of intelligence to all kinds of tasks. The temptation will be to believe that greater intelligence will solve all our future problems. (This is one of the incorrect expectations of the Singularity.) But no matter how much intelligence you have, this thinkism alone won’t solve problems by itself.

Intelligence has to be combined with imagination, perseverance, intuition, and large quantities of data, experience, and context to really be useful. It’s these other qualities that our humanness can supply.

6 Swim

Have a great Weekend when You get to that stage,

Sune