Weekend Food for Thought WFFT

Today's Menu: GPT, China's Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know, AI, Long Form vs Short Form Content and extra insightful sides!

Hello from Lisbon,

I hope you had an interesting and productive week.

1 Getting Visual

2 If You Read One Thing Today - Make Sure it is This

3 Consequential Thinking about Consequential Matters

4 Big Ideas

5 Big thinking

6 Stay with the Questions Longer

A.R. Ammons stated that: “In nature there are few sharp lines. Definition, rationality, and structure are ways of seeing, but they become prisons when they blank out other ways of seeing.”

Embrace the blur for more nuanced ‘seeing’…test it out below…

1 Getting Visual

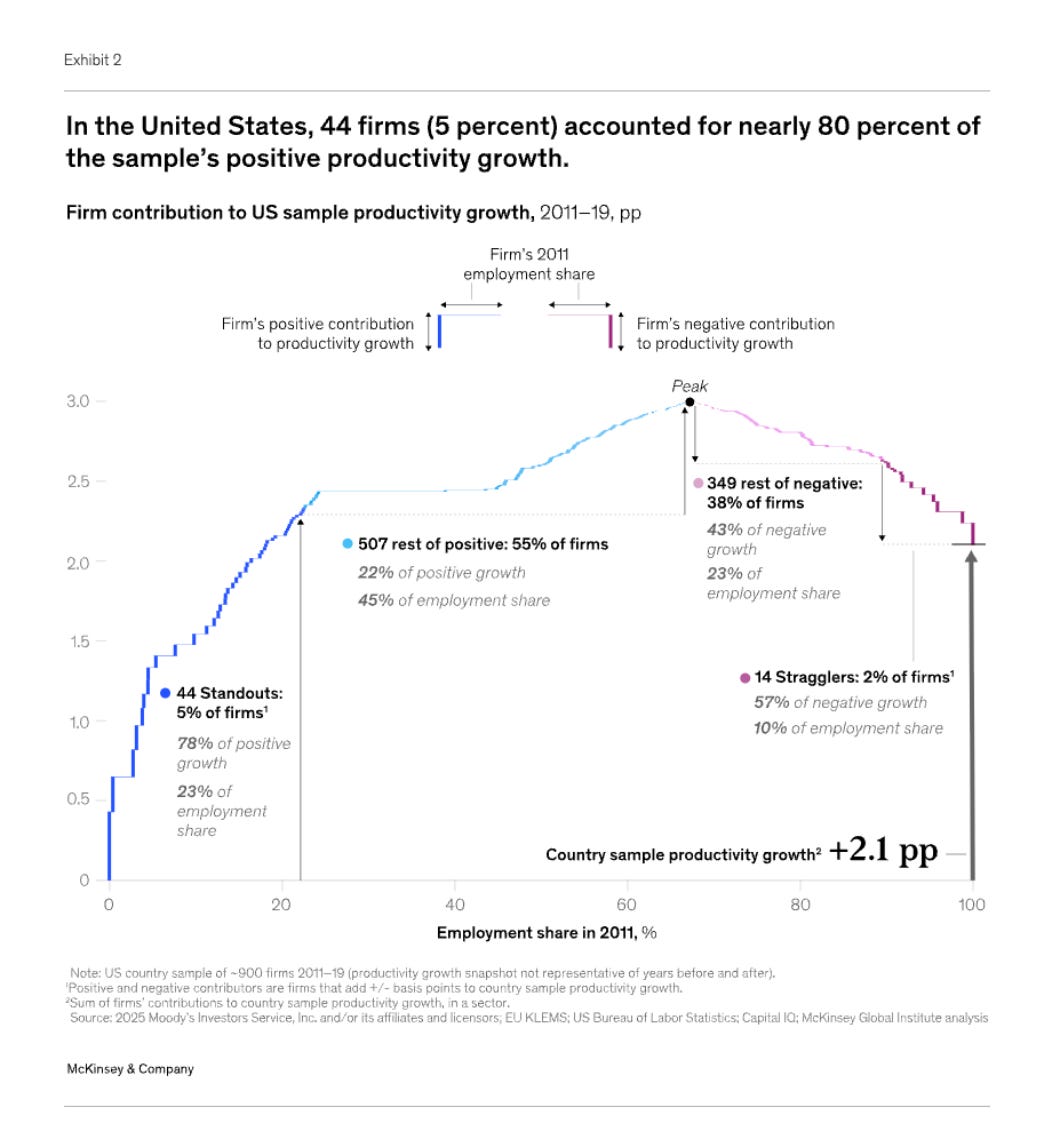

Pareto’s Principle At Scale - “A small number of firms contribute the lion’s share of productivity growth. Fewer than 100 productivity “Standouts” account for two-thirds of growth in our sample of 8,300 large firms in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Many others also play a role: the majority of firms contribute positively.” - McKinsey

The Long View: Productivity & Jobs Growth in the Era of Exponential Compute…

The Exponential Smile - Cost Down. Output Up. AI Model Training Cost & Output…next up: The path of General Purpose Technologies (GPT) = More adoption in broader and broader areas…

US Companies adopting AI - Gradually at first…

The Winning Formula for sustained value creation - Harness the key GPTs…

”Hendrik Bessembinder is an economist who has conducted fascinating research on the determinants of stock market returns in the United States over the past century. His conclusions are pretty simple. Most companies (and by extension most managers) destroy value. Stock market returns are overwhelmingly concentrated, in fact 2% of public companies drove 90% of wealth creation. The outcomes are more stark than that. Last year, while helping some asset allocators think through the AI cycle, I analysed Bessembinder’s results through my frameworks. I’ll share a brief excerpt here, as it’s super relevant. Just two caveats: this analysis is over a year old, and Bessembinder’s data only ran to the end of 2022. Nvidia alone has had a $3 trillion market cap since 2022, which only serves to support the case I made. Regarding concentration, 2% of firms, approximately 600, accounted for 90% of all wealth creation. If your portfolio missed that 2%, and you had backed the rest of the market, you’d have lost money. And the concentration continues, 23 firms (less than 0.1% of the sample), account for 30% of returns. Selection bias - The majority of top performers share a common trait: they are built upon the breakthrough general-purpose technology of the era. Consider the general-purpose technologies of the past 120 years or so: the internal combustion engine, telephony, electricity, and computing. As the table below shows, returns skew heavily towards those firms based on GPTs. The light pink shading represents companies based on the 20th-century GPTs: ExxonMobil, Chevron, GE, and GM—the light blue, Walmart and Home Depot businesses that only exist because of the car. The yellow represents those companies built on top of the GPT of computing. This leaves a handful of other firms. The green signifies the pharmaceutical companies, all businesses that are dependent on investment in research and development and possess deep intellectual property. Visa and Mastercard are shaded in mauve. Of course, when they were founded, they were highly manual businesses, growing as they rode the wave of consumer capitalism; however, their real expansion was enabled by telecommunications and computing. The point is that it isn’t merely that stock market returns are concentrated, with most returns coming from a tiny number of winners. They also cluster around two classes of business: those built directly on the GPT of the era and those that involve deep intellectual property.” - Azeem Azhar

The Power of Process Innovation - As Tim Cook famously remarked, anyone who thinks that a manufacturer like Apple locates its supply chain in China because the labour is cheap, does not understand manufacturing. Apple is in China because of the network of producers that it can collaborate with there. This is partly an effect of policy. Most notoriously the Made in China program launched in 2015. But it is also a self-sustaining process of regional economic development, familiar from network economies and industrial districts around the world. On the scale that it is happening in China, it also reflects the spectacular expansion of technical education and higher education in the STEM disciplines, that is marked both inside China itself and by the huge flow of Chinese students who study abroad, above all in STEM programs. It also marks a significance difference between China and its huge Asian competitor, India, which saw much less emphasis on technical education.

AI Training of Robots is a key bottleneck unlock - China already leads the world in installed industrial robot base - will it harness AI to further push this advantage?

Signs of Creative Destruction or Adaption? “How serious is Google’s ChatGPT problem? AI answers are draining clicks—and dollars—from the web’s long-time gatekeeper. Two years ago, I argued that Alphabet, which owns Google, faced a “GPT Tidal Wave” because “the start page of the Internet is shifting further from the browser and Google.com, replacing dozens or more Web searches each day. ChatGPT is preferable to open multiple tabs from a Google search and continuously backtracking.” I’m an early adopter. Early adopters are either canaries in the coal mine or we’re wrong. Two years on, the data are starting to suggest we’re right. Slides from the investment firm Coatue circulated last week, showing what many of us sense anecdotally: once you adopt ChatGPT, you use Google less. Across a still-short observation window, heavy ChatGPT users have cut Google’s page views by about 8% a year. That may feel mild, yet if the 800 million ChatGPT users today grow—plausibly—to three billion within three years, and if the search deficit holds, Google’s core business could shrink by a fifth, lopping tens of billions of dollars off annual revenue. In truth, that is the bullish scenario for Google. ChatGPT is fast becoming the generic verb for “finding stuff,” and its advantage widens on difficult queries—which may be the very ones that anchor Google’s pricing power. The products will only get better at serving users’ needs, so that 8% figure could rise. Digital history’s graveyard—who kept both MySpace and Facebook profiles running for long?—shows that once a superior interface hits critical mass, dual loyalties fade fast. Usage, in other words, accelerates away from the incumbent. Google is not standing idle. Its AI Overviews now headline many results pages, and Gemini already serves roughly 400 million monthly users (according to Similarweb). And as the table shows, month-on-month growth is scorching. That is serious traction and a textbook example of an incumbent launching a product that partially competes with its own cash cow. Kudos. Yet the manoeuvre muddles incentives: every query answered by Gemini inside Google’s walls is one not monetised by the traditional ads-against-links model. The company made trillions of dollars by being the best at making sense of that linky-web. That web is going, going, gone. Google is too big to disappear with it. The question is: what will it become?” - Azeem Azhar

2 If You Read One Thing Today - Make Sure it is This

Dwarkesh Patel speaks with the thoughtful and insightful Arthur Kroeber, a leading researcher on Chinese tech and macro and author of "China's Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know".

The title is not really representative of the substance and breadth of the conversation. They discuss how China achieved high-tech manufacturing dominance, and where they'll go from here. By Arthur’s account, the Chinese government is like a giant VC fund: they decide on key priorities and then spend hundreds of billions of dollars subsidizing ruthless competition at the local level. They are willing to lose huge amounts of money for a few of their bets to pay off: at China’s scale, effectiveness matters more than efficiency. They discuss the complexities of the US and China relationship and much more - it’s a 2.5hour conversation, but it’s worth taking the time to listen and ponder the many insights and questions raised - do it here:

3 Consequential Thinking about Consequential Matters

Here I consider the perspectives outlined in a couple of insightful explorations on China’s industrial policy and approach to AI in particular. The first is from Kyle Chan (High Capacity Substack) where he looks into how China wants to be the global leader in AI and is deploying industrial policy tools across the entire AI tech stack, from chips and data centers to foundation models and applications. It’s derived from Chan’s work with RAND on a longer form report (Get it here: https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA4012-1.html ). The second piece is by Andrew Stokols (Sinocities Substack) in collaboration with the good people at ChinaTalk. Plenty of consequential thinking on these consequential matters - go explore both in full via the links below…

Some Takeaways:

Key takeaways:

• China wants to be the global leader in AI by 2030.

• But Chinese policymakers are not focused on “winning the race to AGI” (although some Chinese tech companies are, including DeepSeek).

• Instead, Chinese policymakers are focused on building a world-leading and resilient AI industry that will drive productivity gains across the entire economy, from manufacturing and healthcare to education and government services.

• China’s AI policy is particularly focused on “hard tech” applications, such as robotics and industrial automation.

• China is developing its own alternatives to every layer of the AI tech stack driven largely by a need to build resilience to escalating US sanctions.

• Open source is a key strategy for Chinese policymakers and tech firms to catch up with US-led platforms by helping to drive adoption and cultivate a broader ecosystem.

• China is building a National Integrated Computing Network 全国一体化算力网 that leverages renewable energy in western provinces to boost China’s compute capacity but has faced problems with poorly built data centers and still lags far behind US compute capacity.

• State-backed AI labs formed by local governments, such as the Shanghai AI Lab, play a key role in foundational research, creating industry standards, and developing talent.

• Ultimately, China’s AI industrial policy will not only help fuel China’s rapid advancements in AI but will also be critical to the country’s continued progress in the face of growing US-led export controls.

Energy

China’s AI industry enjoys an energy advantage for data centers, driven by aggressive state-backed power infrastructure expansion and the strategic deployment of renewables at large-scale computing hubs.[32] China’s ability to quickly build and connect new power plants removes a key bottleneck for data center expansion that the United States is grappling with.[33] Moreover, China’s energy abundance allows Chinese AI firms to use less-energy-efficient, homegrown AI hardware, such as Huawei’s CloudMatrix 384 cluster.[34]

In 2021, China’s State Grid Corporation estimated that its data center electricity demand would double from more than 38 gigawatts (GW) in 2020 to more than 76 GW, making up 3.7 percent of its total electricity demand.[35] Beijing has made renewable energy expansion and energy efficiency a central focus of its data center expansion strategy, although coal still made up 58 percent of China’s overall power generation mix in 2024.[36] China’s data center build-out benefits from the country’s broader ability to rapidly add grid capacity at scale. In 2024 alone, China added 429 GW of net new power generation capacity overall, more than 15 times the net capacity added in the United States during the same period.[37]

China’s historic success in developing new energy generation and its continued investments in this space suggest that China will be able to meet the increased power demands of deploying AI and could provide subsidized electricity to AI developers and deployers, which could reduce the operating costs associated with AI.”

“Beijing’s support for open data-sharing platforms is likely to play a greater role in advancing China’s AI industry by increasing general access to large training sets without the ownership complexities of a data trading exchange. State support for open data-sharing include open data platforms, such as OpenI, as well as the creation of open datasets, such as FlagData, BAAI’s Chinese multimodal dataset.[85]

Beijing is particularly focused on promoting data-sharing for robotics through such institutions as the Beijing Embodied Artificial Intelligence Robotics Innovation Center and the National Local Joint Humanoid Robot Innovation Center in Shanghai.[86] Several leading Chinese robotics companies, such as AgiBot and Fourier, also have released open training datasets, augmenting the country’s broader pool of robotics training data.[87]"

“U.S.-China competition in AI is seen as the defining technological rivalry of our time. Much of the analysis in this competition is premised on a zero-sum logic — we cannot let China get ahead of us in AI, so the logic goes, as this will inevitably mean the forfeiture of American technological and military primacy.

There is another possibility–China and the U.S. may develop different “varieties” of AI.

For example, the U.S. advantages in cloud computing, software development, and openness to talent (tbd…) give it an edge in development of enterprise software and large language models (LLMs).

However, China has clear advantages in manufacturing and infrastructure, which could offer an edge in what experts term “embodied AI”, or in Chinese jù shēn réngōng zhìnéng, 具身人工智能. Embodied AI systems interact with the physical environment through sensors (like cameras, microphones, touch sensors) and actuators (motors, limbs, wheels, etc.). Embodied Intelligence is shaped by a real-time, physical engagement with the world.

The central government recently included “embodied intelligence” in its work report, indicating the area as a key priority. Zhongguancun, Beijing’s hi-tech area, recently released its plan for embodied intelligence. A recent report by Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) focused on efforts in the city of Wuhan to embody “AI algorithms in real environments. Imbued with the Chinese Communist Party’s predefined values, the AI interacts with its natural surroundings, learning as it proceeds.”

In this post, I explore some of the origins and implications of China’s interest in “embodied AI”, and then present a few examples of this approach in sectors such as autonomous vehicles, personal mobility, robotics, and the“brain-style” AI models being used for smart city operations.

While the current push for embodied AI is part of a prevailing fever for AI globally, China’s priorities reflect long-standing beliefs in the use of technology for solving governance problems, and the need for physical infrastructure and manufacturing as key priorities for the country’s development.”

“The Internet+ Vision is seen as one of China’s earliest national strategies on the application of AI to industry, and underscored the degree to which policymakers in China saw digital data not merely as a sector in itself, but as an input for many other sectors. Li Keqiang’s Internet Plus was also inspired by Industry 4.0, a concept initially proposed in Germany in 2011 (Huda 2023), and which influenced World Economic Forum founder Schwab’s idea of the “Fourth Industrial Revolution” (Schwab 2017). Schwab popularized the idea of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, but the term itself emerged around 2011 at the Hanover Fair as part of Germany’s strategy to use digital technologies to maintain and deepen its edge in manufacturing.

The 4th IR predicted the application of computing technology and the internet to a wider range of everyday life and objects. This encompassed “artificial intelligence, robotics, the Internet of Things, autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, energy storage, and quantum computing.” The concept found resonance in China, a country that, like Germany, was arriving on the world stage as a major manufacturing power.

The idea of the fourth industrial revolution was embraced by top party leaders, including Xi, who saw the coming technological revolution as part of a critical period of changes in world history that China had the opportunity to lead.”

“Jin goes on to note that, “If the 4th industrial revolution is, as Schwab described, ‘5G + the internet of things,’ then China is already leading this revolution, but I tend to be in the camp seeing this as more of a deepening of the 3rd (internet) revolution.” Nevertheless, Jin still saw China as having an advantage over the U.S. due to its production capacity.

“The U.S. still has the best innovation capabilities, but the hollowing out of industry is a big problem. If you cannot turn innovation into products, it’s the same as a piece of waste paper.”

Thus, Jin viewed manufacturing as a crucial component of China’s strength that would allow it to outcompete the U.S. Recently, Tsinghua Professor Tang Jie 唐 杰 repeated a view on China’s advantages as comprising “super-large population, rich application scenarios, and rapid iteration of the end-side ecosystem provide fertile soil for the rapid development of AI big models.”

Of course, the “4th industrial revolution” hasn’t played out entirely as Schwab or China’s leadership assumed. Around 2015, 5G and the “internet of things” were predicted to revolutionize everything. So far, 5G and the Internet of Things have proven less transformational than originally anticipated, but we are still early innings of what could be a longer story in the application of AI to other areas.”

“Robotics is one of the most promising areas for deployment of “embodied AI” and one in which China already has a commanding position. China operates the world’s largest stock of industrial robots, accounting for over 50% of the global total.

Robotic cooking machines have been seen in China for some time, tossing bowls of noodles.

So what’s different now?

According to Grace Shao, “embodied AI robots are trained on real-world data that uses reinforcement learning and they have developed the ability to “think. Recently, the Huisi Kaiwu platform was unveiled in Beijing as the world’s “first general embodied intelligence platform” for interfacing with robotics and other devices. The idea is that robots could be programmed and customized through this platform to handle specific tasks. The project is overseen at the Beijing Innovation Center of Humanoid Robots, jointly funded by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the Beijing municipal government, and other private firms and research institutions. In Shenzhen, Huawei (Shenzhen) Global Embodied Intelligence Industry Innovation Center began operation in 2024 and has cooperation with Shenzhen-based robotics firms Leju Robotics, Zhaowei Electromechanical, and Daju Robotics. Leju’s humanoid robot Kuafu (夸父) apparently offers 5G compatibility, which would facilitate data collection and training of robots for industrial applications.”

Implications of Embodied AI with Chinese Characteristics

1. Diverging Models of AI Development, and bifurcation in global AI trajectories: The U.S. centers on abstract, cloud-based intelligence (e.g., LLMs), while China develops AI tightly integrated with physical systems and infrastructure. This divergence has implications for technological standards, ethics, and the global diffusion of AI technologies.

2. Infrastructure as an Advantage/Differentiator: China's infrastructural focus enables deployment of AI in real-world contexts at scale, especially in mobility, urban governance/management, and robotics. This presents a comparative advantage not often captured in typical U.S.-China tech rivalry narratives.

3. Legacy of Cybernetics and Systems Thinking: The enduring influence of cybernetic thought — from Qian Xuesen to current smart city projects—reveals a unique continuity in how China views technology as a tool for social coordination and governance.

4. Human Capital Bottlenecks: Despite policy support, China faces challenges in high-end software and algorithmic talent. The article notes concerns about the availability of top-tier AI engineers, which may limit scalability of embodied AI initiatives.

What can the U.S. learn from China’s approach to AI?

So far, U.S. application of AI has focused largely on LLMs and application of AI in enterprise software. This means AI could be monopolized by tech platforms like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and OpenAI. AI is being embraced across a wide array of sectors. Diffusion of embodied AI could even make efforts to reshore manufacturing more feasible, with the caveat that it would employ fewer workers and offer fewer well-paying jobs.

Conversely, a failure to incorporate embodied intelligence could mean American manufacturing becomes even less competitive with China’s increasingly advanced factories.”

4 Big Ideas

The McKinsey Global Institute (ChatGPT has not replaced them entirely just yet) takes a look at ‘The power of one: How standout firms grow national productivity’ in this recent report - worth a skim in full, do it here:

Some Takeaways:

— When firms become more productive, so do economies. Increasing the value each worker creates also promotes rising wages for workers and profits for firms. These facts are well known to economists. Our other findings are not.

— A small number of firms contribute the lion’s share of productivity growth. Fewer than 100 productivity “Standouts” account for two-thirds of growth in our sample of 8,300 large firms in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Many others also play a role: the majority of firms contribute positively.

— Productivity grows in powerful bursts as firms find new ways to create and scale new value. Think Apple expanding into services, easyJet shaping the discount airline trend, and Zalando pioneering apparel e-commerce. This is not the efficiency transformation nor the gradual diffusion described by conventional wisdom.

— In the United States, the most productive firms expanded and unproductive firms restructured or exited. This contributed half of US sample productivity growth while sticky under performers dragged down growth in Germany and the United Kingdom.

— This fresh view of productivity growth calls for a new playbook. It suggests focus on the power of the few more than the broad swath, on value creation more than efficiency, and on reallocation of resources to leading businesses.

“The world needs robust productivity growth more than ever to address pressing global issues: inflated balance sheets, financing the transition to net zero, bridging empowerment gaps, and funding a demographic transition with more retirees and fewer workers. And a fundamental unit of productivity growth is firms. If firms do not increase their productivity, economies don’t, either.

Firms themselves benefit from productivity growth, or growth in value added per worker. In view of long-term demographic shifts and the tight labor markets of today, labor productivity is a strategic imperative.2 And productivity growth is the only way for businesses to serve all their stakeholders, delivering rising wages for their workers, increased customer surplus, and profit. Customers and employees are typically the biggest and most immediate beneficiaries of productivity growth. Productivity growth is a win-win for all.”

“The relationship between Standouts and sector growth is, of course, a symbiotic one. Standouts drive the growth of sectors, but some sectors also have the market dynamics, technology, regulation, and competitive setting that provide fertile ground for Standouts. There were more Standouts in sectors where firms could create new customer value and scale new business models than in sectors that were mostly about efficiency. For instance, the US computer and electronics sector came with many scalers and disruptors. Often when demand is faltering, other sectors are relative deserts, tending to produce more Stragglers or firms that restructure.”

“Bold strategic moves often trigger chain reactions that lead to bursts of productivity over specific periods and sectors in a pattern of “action and response” more than through the diffusion of practices.”

“Leading firms and the dynamic reallocation of employees toward them matter for growth

Beyond the presence of Standouts and absence of Stragglers, the following patterns characterized subsectors and countries that posted rapid productivity growth:

— Frontier firms contributed disproportionately. In the highest-growth subsectors, the primary pathway to productivity growth was firms contributing from the frontier, followed by firms transitioning to it.

— Leaders pulling ahead drove rapid subsector growth as often as laggards catching up. A common view is that productivity growth is particularly strong when the broad swath of middling or lagging firms catches up or converges with innovative leaders as best practices and technologies cascade down. Such convergence appeared in four out of nine subsectors with fast growth. In

the other five, rapid growth came from frontier firms pulling further ahead—divergence.

— Employment reallocation from lagging to leading firms mattered nearly as much as productivity advances within firms and more than new entries or exits. In almost all subsectors, both productivity advances and employment reallocation played a role. In eight of 21 subsectors with positive productivity growth, reallocation of employees from less to more productive firms dominated. In the others, productivity increases by individual firms mattered more.19 Firms leaving or entering the market—traditional creative destruction—mattered less. It is notable that, in virtually all positive-growth subsectors, exits added to growth, sometimes substantially, while in almost half of these subsectors, entries detracted from growth. New entrants proved too small or unproductive to leave a mark during the 2011–19 snapshot period. Over a longer period, every Standout will have been a new entrant at some point, but the youngest firm in our eight-year sample was 11 years old, and the average was 58.”

5 Big thinking

Ted Gioia AKA ‘The Honest Broker’ shares some interesting and contrarian perspectives on the trends in content and the shifting dynamics in the audiences’ engagement with longform content vs the prevailing narrative of an addiction to shortform. As a card carrying member of the Longform Appreciation Club (for anything besides Zoom meetings and queues) this is welcome news and something I have observed in my own teenagers and young adults areas of interest and content intakes…Go ponder it here in full:

Some Takeaways:

“The rebirth of longform runs counter to everything media experts are peddling. They are all trying to game the algorithm. But they’re making a huge mistake.

They believe that longform is doomed. They see that digital platforms reward ultra-short videos on an endless scroll. And they understand that this works because the interface is extremely addictive.

So short must defeat long in the digital marketplace. That’s obvious to them. But all the evidence now proves that this isn’t happening.

Many media companies went broke trusting their advice. It was dead wrong—but many still haven’t figure out why.

Let me lay it out for you. Here are the five reasons why longform is now winning:1. The dopamine boosts from endlessly scrolling short videos eventually produce anhedonia—the complete absence of enjoyment in an experience supposedly pursued for pleasure. (I write about that here.) So even addicts grow dissatisfied with their addiction.

2. More and more people are now rebelling against these manipulative digital interfaces. A sizable portion of the population simply refuses to become addicts. This has always been true with booze and drugs, and it’s now true with digital entertainment.

3. Short form clickbait gets digested easily, and spreads quickly. But this doesn’t generate longterm loyalty. Short form is like a meme—spreading easily and then disappearing. Whereas long immersive experiences reach deeper into the hearts and souls of the audience. This creates a much stronger bond than any 15-second video or melody will ever match.

4. All cultural forms create a backlash if they are pushed too far—and that is happening now with shortform media. People have digested too much of it, and are ready to exit for the vomitorium.

5. People now view anything coming out of Silicon Valley and the technocracy with intense skepticism and resistance. The pushback gets more intense with each passing month. This resistance has already killed the virtual reality market (despite billions spent by Meta and Apple), and will soon impact many other tech services—especially those based on turning the public into scrolling-and-swiping chimpanzees.

Longform isn’t like a drug. It’s more like a ritual. Instead of promoting addiction, it possesses a hypnotic power that creates an almost cult-like devotion among its audience.

Just consider the obsessive fandoms of Wagner’s Ring, Proust’s prose, Joyce’s daylong Dublin stroll, the Harry Potter novels, Christopher Nolan’s movies, DFW’s Infinite Jest, Beethoven’s Ninth, Taylor Swift’s concerts, etc.

No TikTok will ever generate that kind of passionate long-lasting response. They come and go. But longform fandoms will last a hundred years or more, and get passed on from generation to generation.

That’s why longform is making a comeback—in total defiance to the wishes of Silicon Valley and their scroll-driven strategies. Maybe that should be a lesson to them. Perhaps they should reconsider some of their other social engineering initiatives before they also meet with a painful reversal.”

6 Stay with the Questions longer

Have a Great Weekend When you Get to that Stage,

Sune